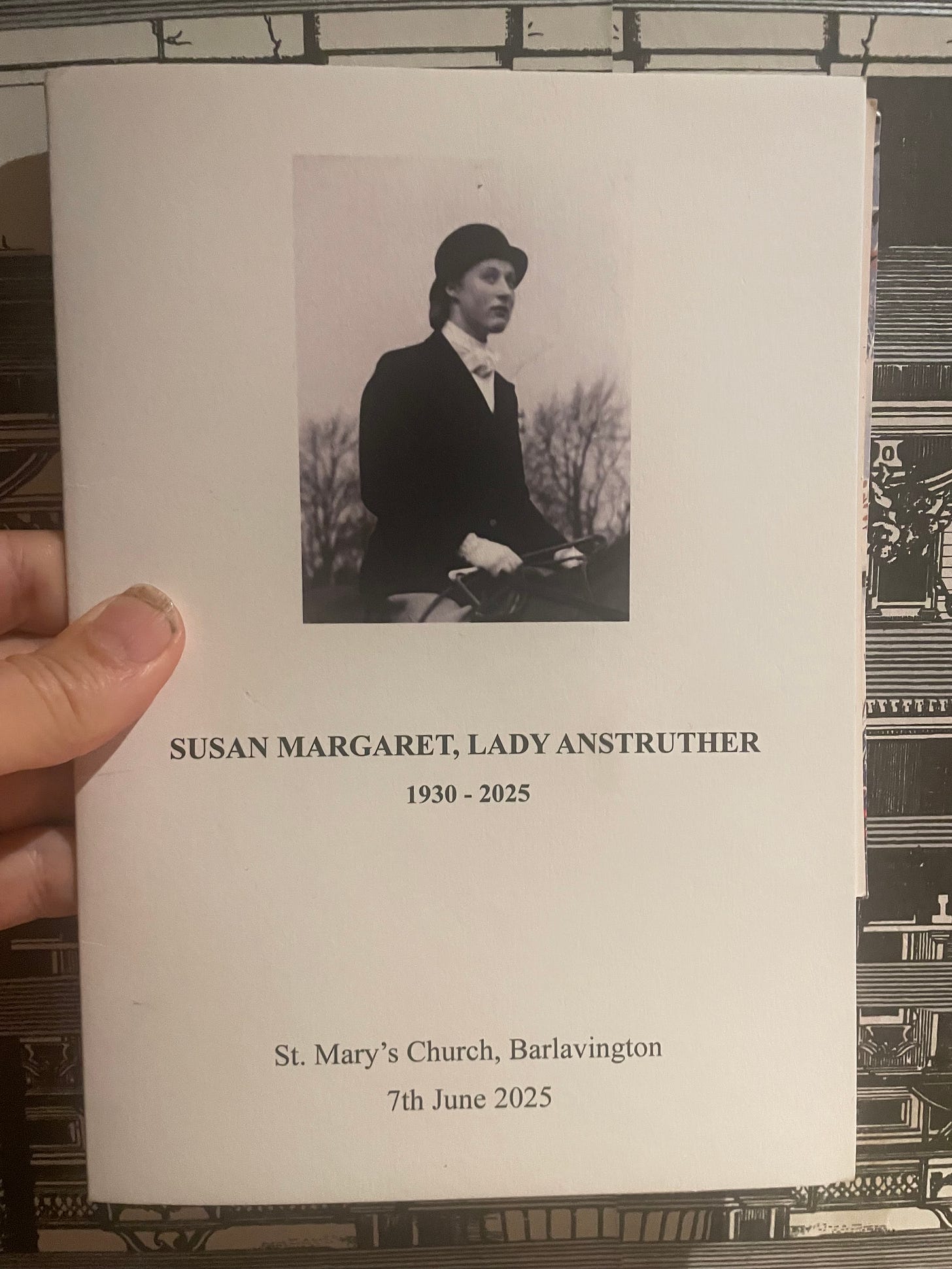

Remarkably, earlier this week a friend of the family found that bowler hat while cleaning out a cupboard. My mother had leant it to her years ago and they’d both forgotten. The friend didn’t know we’d choose that photo for the order of service and we didn’t know the hat still existed, but yesterday, outside the church, she handed it to me. I put it on. It fitted perfectly. I wore it all day. Amidst the profound and sombre shock of death, the presence of goodbye, it brought a touch of clockwork orange to the atmosphere, a dark humour that equally fitted all that has been. I loved it. I’m sure she, or someone, arranged it to be so.

There’s much more I’m going to say about the funeral in the coming days, but for now I’m just going to post a copy of the eulogy and the 1958 protest march to Aldermaston in which she appears at the end.

In a life as long as our mother’s there are bound to be multiple versions, as many as there are stages from daughter of Peggy and Harry to the Dowager Lady A, mistress of the hunt. She was born Susan Margaret Paten on 10th June 1930, the eldest of four, a childhood at Thornfields, the house in Castor just outside Peterborough which her father designed and built. She said being brought up on a building site made her an architect.

She described something idyllic despite the war; a home brimming with claret from the family hotel and wine business, a magnificent garden which informed her sense of scale, a pony and trap, hunting in plaits, feeding the pig which would later be eaten nose to tail, everything but the squeak. Her favourite pony, Rob Roy, her favourite black Labrador, Battle. Picnics at Stonehenge spilling yoghurt on ancient monument, a stop off on the drive to Cornwall, family holidays by the sea. She was stoic in her telling of being sent to school at eight, her suitcase snapping open on her arrival, spilling her childish possessions all over the floor, but the experience made her educate her own children differently. She refused to send us to boarding school, it was a battle she won, unlike that with her own father who insisted she go to secretarial college when all she wanted was to get her out her Rotring pen & set-square and start designing.

Perhaps the only time in her life she did as she was told, she acquiesced to his wishes and learnt to type, a skill preceded by a year sailing on The Black Dragon with her uncle and followed by another on a fruit farm; perhaps it was the experience of picking raspberries and redcurrants that made it an essential of our childhood. But this was long in the future. At 21 years of age she hightailed it to London, to a flat in Eccleston Square shared with those who were to become her lifelong friends. One of only four women at the Middlesex Polytechnic on Regent Street, she qualified as an architect and met her first husband, fell in love with Johnnie and became Susan Walker; not much culinary skill but living in young bliss. Her mother-in-law, worried for their diet, sent roast dinners down from Haywards Heath by train, a plate of chicken and vegetables covered with a cloth and collected from the carriage at Victoria station. Her first job as an architect was in the office of Ernő Goldfinger. It ignited a lifelong love of Brutalism, a unity of form and function which described her working life. Susan Walker was an activist and political firebrand; she joined the Labour party and CND. She walked from Trafalgar Square to Aldermaston in 1958 to protest the nuclear arms race. A film was made of it, she went to the cinema to watch the newsreels and there she was, filling the screen, young and idealistic. Full of belief.

Susan Walker didn’t disappear when Johnnie did. Her marriage ended but the name carried on. I remember her telling me how he was killed in a car accident, and the pain in the room spoke more than she did, it filled in the gaps. Susan Walker Architects, her professional practice in London, was her love letter, a happy place, a determined passion even as she began another. She married our father, Ian Anstruther, introduced by one of the Eccleston Square flatmates. On the day they met he was chopping wood by the shed in his Sussex garden. She didn’t know he’d never done it before nor ever would again. He was an answer. Together they built another life.

As Susan Anstruther she had six children of her own; Lucy, her second daughter who lived for just three days was the only one missing in the noisy, chaotic home she created in Thurloe Square. She moved amongst a wider family of us; mother and architect, her leather attaché case had both initials, one on each side. She once turned up to a flight but was denied travel - while her passport was Susan Anstruther, her tickets had been booked for Susan Walker: this was how closely she ran these parallel lives, although the latter felt dominant. The dining room was taken over, the white round table stacked with her papers, endless meetings for a multitude of committees. The coffee table slipped with piles of Private Eye and the Architect’s Journal. This version of Susan drove a Mini which she regular misplaced and failed to lock; more than once it proved a handy bed for a stranger who sat up in the back on our way to school. Susan Walker was unfazed. She was tenacious and focused, she frequently missed supper only to be found asleep at her desk in Walton Street and later, Cromwell Road. Holidays to France were by way of Corbusier and every Romanesque church from Calais to St Tropez. Simon and Garfunkel on the tape machine, brown bread sandwiches on the side of the road. Even by the pool, she worked.

Yet while she made other people’s houses complete, for her own, string made up for most things. The oven door was made good with bailing twine, the fridge not working was met with a reminder that, The cobbler's children have no shoes, and any complaints from us resulted in being sent for a run round the block. When they married, our father said, One thing you must not do is hoover on a Sunday. Little did he know that she would never hoover at all. With two fingers up to authority, school notes were written on old envelopes and sandwiches wrapped in the innards of Weetabix packets. Clingfilm could perfectly well be hung on the line and the same wrapping paper returned every Christmas. She was an agitator, an environmentalist, a child of austerity and way ahead of her time. Domestic, she was not.

What she was, as Susan Anstruther, was deeply involved in the community and wider world causes. She was a governor, and later Chair, of Marlboro Primary School, an involvement that stretched for over forty years. She was a Trustee of the Georgian Group and Fagus Trust, a founder of the Thurloe Square Leaseholders’ Association and an active voice on the Square Garden committee. But more crucial was her immediate sense of opening her home to anyone in need of care. It was never just us in that tall house in London. She supported a multitude of students, refugees, artists, friends and friends of friends, and many total strangers. She was a flag bearer for the needy and her open door policy meant the house was always full. She loved it like that, and as we left home our rooms were taken by others.

But during those years of our childhood, political discourse was the order of the day at the kitchen table. She had knowingly married a Tory and it made her natural born socialism harden into lines in the sand. Merrily she’d tell me how at weekend parties in the Sussex domain of our father she’d seat Conservative voting guests under the low beam of the dining room so that when they stood up from dinner they’d crack their heads and leave bleeding. Our father said he didn’t mind marrying a socialist because he cancelled out her vote. She didn’t find that funny, but together they upended traditional roles, and arranged what worked for them both. She mostly lived in London with us while our father was mostly down here, in Sussex. At weekends we all got together, while he would occasionally come to London, a lemon in his pocket, moving silently through the throng.

There was an era of parties in London too, bohemian affairs in the drawing room of artists, writers and actors, and years of exhibitions in the basement; in our father, she found a cultural alignment; both clever, both passionate supporters of the arts. Every year another winning painting was added to our walls from the prize they gave to students at the Royal College of Art. They both loved the opera, and Glyndebourne became a much loved ritual she continued until the end. She also started riding again, and right around that time, at the death of our father’s cousin, became Lady Anstruther, the fourth iteration of her life.

Daughter, architect, wife, mother, card carrying Labour Party activist, campaigner for the SDP, and now a signed up member of the British aristocracy. You’d have thought that would have riled, but it didn’t. Lady Anstruther hunted. She became embedded in Sussex life, she turned her architectural efforts to the roof of this church, she became a regular presence at Petworth Festival, her lifelong love of music turning its attention to local recitals as much as those at Wigmore Hall. I asked her, who did you prefer, Lady A or Susan Walker? and she replied, Both.

Weekdays in town, weekends in the country, five children lying like sardines in the back of her Citroen from London to Sussex on a Friday night, spilling blinking into the light of the low-beamed cottage to take over our father’s silence with our shouts. She baked bread with a hole in it, roasted pheasant from the hanger, burnt carrots from the garden, served up unidentifiable greens, and finished it all with redcurrants from the fruit cage, sugar on the side. Jam making season saw vats of blackcurrants boiling. The garage shelves were filled with jars of chutney, the chest freezer packed with venison and crumble. She stocked up and eked out. A child of the war. Stuff and nonsense was her approach to health and safety. She broke her ankle but refused to accept it, walked around on it for a week until warned she’d be in a wheelchair if she didn’t get it seen to. Lady A was a horsewoman through and through, a return to her girlhood for the sake of ours; we rode for hours on the Downs, got togged up for hunt meets, came home exhilarated, covered in mud to eat boiled eggs by the Aga, and our father asking, Did you fall off? May was the hunter she bonded with most deeply: on May, Lady A was mistress.

From all these worlds she had many friends and admirers and those who stood in awe. She had bite, she was fierce, the simple use of Oh, could cut you to the quick. She was a feminist icon and could be wildly unfair. She believed in a left wing state and kept a house in the south of France. A true claret socialist, she was a conundrum. When our father died she carried on the weekend routine uninterrupted, unchanged but for the absence of him. But when Covid hit she moved here, to Sussex, and never went back. She closed Susan Walker Architects aged 90 and became the original Dowager Lady A.

And that was how she lived out the last five years. Springs her full time home, as mobility declined her vegetable garden was brought nearer; lettuce and radish from the terrace, the rock garden singing its endless song as she sat in the sun, the best of care around her, the Guardian newspaper open on the table. She spoke of childhood, family, her grandchildren, us. Her life as a daughter, architect, activist, wife, mother, urban agitator and pastoral huntswoman, grandmother, gardener, mistress of all she surveyed, came together in a Sussex landscape. Through it all ran her will of iron, a determination and strength that she gave to each of us, that we carry on. She was forceful, determined, and sharp as a whip. She was happy, cared for, and loved. And the birds sang in the morning and the sun shone, and the doors were opened to the garden as she left.

Here’s the film of the 1958 protest march to Aldermaston.

Gathering

I keep feeling I should be feeling more something, but like mother like daughter I am back on the horse quick smart this Monday morning, enough of that, there is work to be done. The novel I have wrestled with has been sitting quietly waiting. This morning I got up to meet it. It felt good to be in its company again. I have returned to the beginning to pick up the thread of its tone, I am combing through to find where I went wrong which funnily enough is what’s about.

Eleanor, your eulogy was a model of the magic of detail to summon forth image after image of the person in action. You gave us a movie in words of your mother in all her different roles. Yet there is a through line of her personality running through it. One favorite phrase: "spilling blinking into the light of the low-beamed cottage to take over our father’s silence with our shouts."

Wow what a life. So many amazing details. ❤️