Peggy was waiting for her outside her house, two doors down on Hampton Close. She jumped off the low wall when she saw her. Miss Jenkins had said to meet them at the roundabout, Peggy’s mum would be driving the minibus. She’d pick everyone else up and meet the girls last. She’d also said, Call me Annabel only Bridget couldn’t do that. No way.

Peggy’s hair looked like she cut it herself, jagged and misshaped. Her satchel was covered in badges.

“Where did you get them?” Bridget spoke quietly. She sounded like her mum. Her breath made clouds. They couldn’t see further than their hands, it was so foggy. The streetlights cast an orange glow.

“My mum’s a member of CND and the Labour Party and Women For Peace and Amnesty International and Greenpeace and The Fabian Society.”

“What’s Amnesty International?” Bridget hadn’t heard of any of them.

“It’s where they find people being tortured and rescue them.” Peggy moved her satchel to her other shoulder. It was the first they’d spoken ever. At school they ignored each other.

“Cool,” said Bridget.

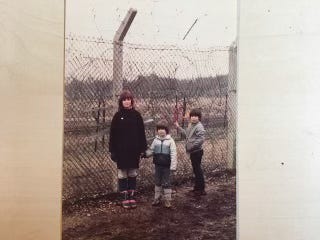

They reached the roundabout. It was freezing cold and damp, a constant feel of drizzle in the air though it was impossible to tell if it was falling or rising. Bridget had forgotten to wear gloves. She’d forgotten to eat breakfast too. Her fingers were so cold she could hardly feel them.

She wished she could think of something else to say, but nothing came and she tried not to copy how Peggy kicked a stone off the pavement as they waited, tried not to say, Cool again as it skittered across the roundabout and bounced perfectly onto the concrete, hitting the poles of the sign that said, Welcome to Surbiton. Early morning van drivers whooshed past, the drivers leering. Peggy scowled and Bridget felt uncomfortable everywhere, with everything, the attention and lack of it, the never knowing what to do.

“So your mum’s into all that,” she said, trying to mumble and speak clearly at the same time so that Peggy would hear, but not think she cared.

But Peggy didn’t have to answer, to pretend she hadn’t heard her or say anything because a white minivan blinked its indicator, swung off the roundabout and came to a halt beside them, the door opening before the van had stopped.

“Jump in!” Cried Miss Jenkins, as if they were on a runaway cowboy film and couldn’t wait for more than a second. Damp, drizzly rain, an orange glow to the morning light, Peggy and Bridget scrambled for the door, Peggy leaping first, swinging off the bar put there for old people, and being swallowed by the van, straight to the back, leaving Bridget to take the only seat empty, at the front, behind the driver, beside Miss Jenkins.

Peggy’s mother at the wheel had a head scarf on. The bus was full of women.

“Excited?” asked Miss Jenkins.

Bridget didn’t know what to do with her face.

“Have you got the note?” Miss Jenkins held out her hand.

Peggy’s mum put the bus into gear. Bridget pretended to look for the note in her bag as the minibus swung a U-turn, crossed the roundabout and took off in the direction of who-knew-where; Bridget never looked when she went on trips with her family, the campsite in summer, her dad’s mum at weekends. That’s all they ever did, the only trips they ever seemed to go on apart from Center Parcs with her dad that one time. If someone asked her which way was north she wouldn’t have a clue.

She kept looking for the note until someone in the back started singing and Miss Jenkins got distracted like a dog with a biscuit and started clapping and singing along in her thin reedy voice that Bridget would have given anything not to hear.

She’d acted like she didn’t care when her dad said no.

He’d said “I’m sorry Bridget but I’m afraid not. We can’t risk it. Not in these times. You wouldn’t want to be separated from us, now would you?”

And she’d nodded as if she was still a child and she’d let him touch her cheek with his knuckle in that gentle way he had that said, No hard feelings.

Things like that kept him happy, like her mum said they would. Now that she’d seen it once she saw it everywhere, how her mum did all kinds of things to keep him ticking along in his made-up world, why she said, Just go along with it, Bridge, and gave her a look like now she was older she could understand. It was as if all this time she’d thought her mum was a bit thick and her dad was the boss when actually her mum had this secret control room at the back of their marriage where she pulled all the levers, while the levers her dad pulled were pretend ones like the toy steering wheel he’d got for Paul. What she couldn’t understand was why her mum bothered and how she could be so boring as to let her dad walk all over her. And the brief flash of seeing who was in control was suffocated by the feeling that her mum must be stupid actually otherwise why would she bother.

The only thing her mum seemed to do that was for herself was go to church. She’d be off out this morning and Bridget had already said she wasn’t coming, as if she was upset at not being allowed on the school art trip.

Her mum had said, “Never mind,” and she knew she’d let her sleep in, or think she was letting her sleep in anyway and not notice for ages she wasn’t there. And her dad had promised to take Paul to football again after her mum had said, It’s not as if world war three will notice if you miss a Sunday testing whistles, but the neighbours certainly will, and so as far as Bridget reckoned, none of them would check on her till it was time to go to see her dad’s mum and by then it would be too late, and she’d probably be back by then anyway so it wouldn’t matter and even if she wasn’t she’d be back soon after that, so it was probably going to be all right and even if it wasn’t she didn’t care.

Peggy’s mum put a tape on and the same song came over the speakers and everyone started singing again. It went on about the spirit and being a mountain. It sounded like one of those hippy songs they did in country dancing at the juniors. It was nothing like The Jam or Echo and The Bunnymen; it was reedy and high pitched; it was women’s voices like the Joan Baez records that Miss Jenkins had tried to make them listen to once in class saying it would make them paint better.

“I recorded it last night,” shouted Peggy’s mum.

Kate Hilperton was the kind of mum who looked more like Peggy’s age than a mum age even though she was probably older than Bridget’s mum. She wore a headscarf like off The Waltons and she was all chit-chat as if she didn’t care who she spoke to, whether it was a grown up or a child. She sang loud over the noise of the engine and the music, and they all joined in the chorus of, She is like a mountain, like they all knew it. Bridget didn’t join in. She’d already been told she couldn’t sing at school when the music teacher made them sing on their own to know which group to put them in, and he’d put Bridget right at the back and told her to do it quietly, so there was no way she was singing now, being right up the front of the bus next to Miss Jenkins.

Miss Jenkins said, “Come on Bridget! It’ll keep you warm,” but she was warm enough already, or sort of, not really but she still wasn’t going to sing.

Wonderful immersion in Bridget’s family these last few installments! And this pure teen logic - Who can resist? 😅“she’d probably be back by then anyway so it wouldn’t matter and even if she wasn’t she’d be back soon after that, so it was probably going to be all right and even if it wasn’t she didn’t care.”

I’m swept up in the adventure, the movement forward, layered with more about Bridget and her family. This line: “It was as if all this time she’d thought her mum was a bit thick and her dad was the boss when actually her mum had this secret control room at the back of their marriage where she pulled all the levers, while the levers her dad pulled were pretend ones like the toy steering wheel he’d got for Paul.” = so good!!