It was daytime when they left the motorway and turned off at a sign to Newbury. It didn’t look anything like the north Bridget was used to. When they went up to RAF Molesworth, the houses were made of bits of stone as if grown from the earth in pebbles, but this looked like they’d hardly left Surbiton. And they’d got there faster.

“Are we near Kettering, Miss?” She wanted Miss Jenkins to think she was well travelled.

“Kettering?” Miss Jenkins opened up her fold out map that she’d been using to tell Peggy’s mum left or right or straight on. It was nothing like her dad’s fold up maps. Her dad would have a fit if he saw it. It was torn on every corner. “That’s up north, Bridget. We’re west. Berkshire, I told you.”

Bridget thought all military bases were in the same place. How was she to know. But they were pulling in at an Esso garage and horns were blaring and the whole forecourt was full of women piling out of vehicles, hugging, blowing whistles like the ones her dad had. A couple of them unfurled a banner that said something about peace only it was hard to see because they kept jumping about. On the other side of the forecourt was a Happy Eater. Bridget would have given anything for a full English, but she hadn’t brought any money with her, either. A woman emerged through the swing doors. She had the kind of haircut that got you stared at, shaved, spiked, blonde.

“Anyone need the bathroom?” Miss Jenkins stood up as if it really was a school trip. Bridget did, but didn’t dare, in case the bus left without her. The others filed past, joined the party on the forecourt, streamed off in different directions but Bridget sat tight. She watched the blonde, spiked woman dance about wearing a banner as a cloak, as if she was free to do anything she wanted. When she skipped past Bridget’s minibus on the way to her own, Bridget saw her ears were pierced all up the sides.

And then the engines started again and everyone got sucked back up onto their busses and then they were off, a convoy of whistles and waving, off on the road that wasn’t a motorway anymore but winding and getting busier with normal cars and normal people all staring at them as they wound through country lanes.

Miss Jenkins sat sideways in her seat, she was wearing jeans. Bridget felt embarrassed for her and turned away but Miss Jenkins tapped her on the leg. “So, what did your mum say? It would be so good to get her on board, Bridget. She could get the other dinner ladies involved too and that’s almost half the female contingent at school already. Do you think they’d be interested if I held a meeting? I’m sure David, I mean Mr Whittaker, will have words,” now it was her turn to be embarrassed that she’d used the headmaster’s first name in front of Bridget. She skewed her mouth as if she was trying to decide whether to let Bridget in on the secret that all the teachers had first names, as if Bridget didn’t realise that, as if she didn’t know that behind the staff room door, they all had this life that wasn’t just being teachers. “We could hold a meeting,” continued Miss Jenkins, “if you could get all the kids involved, all the girls especially. Who are your friends, Bridget?” And then she looked even more embarrassed because it was obvious that Bridget didn’t have any friends, everyone knew that. “Anyway,” she patted her leg again, “let’s see how today goes. I’m so thrilled you wanted to come. I’ll pop in to find your mum tomorrow to thank her.”

“She’s not in tomorrow.”

Miss Jenkins waited.

“She’s got a cold.”

“Oh, poor thing. All right, but you be sure to tell her tonight that she’s done something really great, letting you come and see, letting you be part of history. We need all the bodies we can get, all the women. Women only, Bridget! Can you imagine?”

Bridget didn’t have to imagine. The bus was slowing down. They were coming up on a woodland and all the vehicles were pulling in and finding somewhere to park. There were coaches, lines and lines of them like the carpark at Alton Towers. Peggy’s mum parked up and turned around in her seat. Her headscarf had slipped on her head. Her brown hair poked out the sides.

“For those of you who haven’t been here before, this is Main Gate, or Yellow Gate as it’s called. We’ll be stretching out around the whole nine-mile perimeter. It doesn’t matter where you go, find a patch of fence and tie whatever you’ve brought to it, walk along the line, find your place but if you’re wanting a lift home tonight, I’ll be leaving at sundown, that’s about half three,” she looked at her wristwatch. “There’ll be plenty of others if you miss it.”

But no one was listening to Kate Hilperton. They were standing in their seats, they were peering through windows, disgorging through the door onto soggy land, among wet trees, into a day lightening with damp winter and thousands of other women, their faces wrapped in scarves, their bodies packed into coats but unmistakably women, everywhere. And Bridget moved with them out into the sweet forest air, a bramble-land dotted with tents, ragged with tarpaulin that flapped and mixed with camp fire smoke, flames that crackled against drizzle, a front room transported to a forest floor, armchairs, a sofa and a bench and beyond it a chain link fence as high as a school wall, higher even which cut across the earth, a straight line in bending woodland topped with barbs that would pierce your palm, a wild and ragged forest floor and a manmade slice and beyond it nothing, a land stripped. Two worlds colliding at a chain link fence, earth to tarmac, women to squaddies who stood watching the wave that brought Bridget with it, her hands reaching forward, her fingers curling around metal.

The singing began. Perhaps it had never stopped. There was singing beside her and behind her and hands gripping the fence like her hands gripped it, fingers intertwining through the chain link, faces pressed close. The woman beside her was crying. She held a photograph of two children smiling in sunshine, posing for the camera, the arm of the bigger one around shoulders of the littler, the little one in red shorts like the ones Paul wore that had been Bridget’s once, and the woman had pierced the corners of the photograph and threaded them with white wool, and she was tying it to the fence. Bridget looked up and down the line and the same was happening everywhere, banners being strung, photographs pinned as far as she could see, women pressing up against it, hands moving, string and wool and things appearing, tying, and pinning and making an art of this fence that had on the other side a yawning stretch of nothing, tarmac, blankness, hard square lines and men.

The press of bodies warmed her. She’d forgotten her cold hands and empty stomach. She felt someone tugging at her jacket.

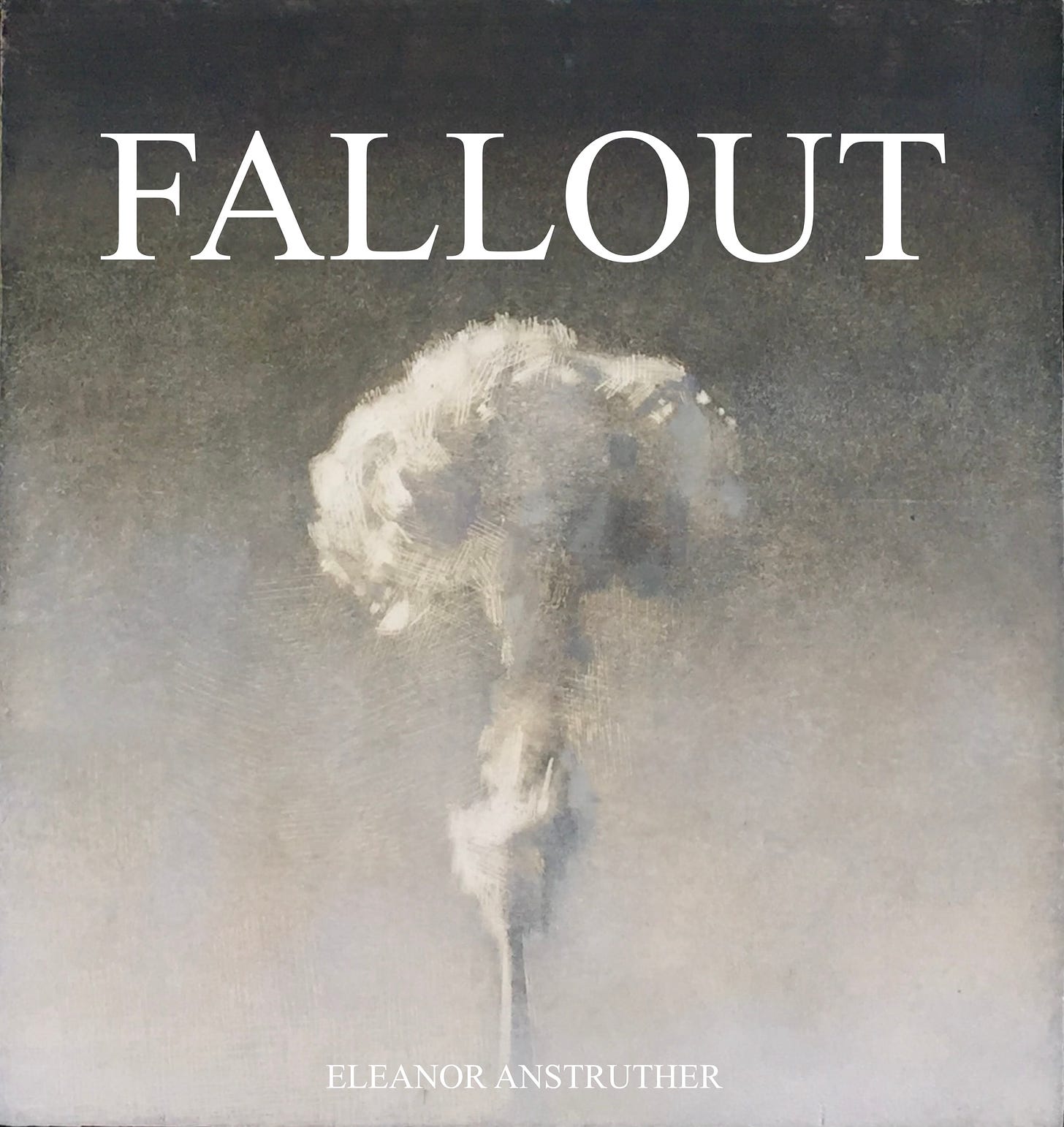

Thinking about that fence, and the vivid way you depicted it, almost feels like a work of art. Women never fail to tell stories, take a stand, move mountains, AND make it look and sound and smell beautiful in the process.

That photo! Just amazing.