“It’s for my art O-level project, mum.” She held out the note Miss Jenkins hadn’t written because that one was in a rubbish bin by the bus stop while this one, she’d written herself from a torn-out page of her chemistry book, sitting on a half seat in the bus shelter, the page on her lap and having to do it twice because the first time her pen went through the paper onto her school skirt. There was no way she’d be allowed to go off to some women’s camp with Miss Jenkins and Peggy Hilperton’s mum. She’d written it was for a school trip to the Tate.

She’d done a better job the second time, impersonating Miss Jenkins’ handwriting which was spidery like everything else about her; spidery and mousey and corduroy and red. The one Miss Jenkins had written was stuffed in a MacDonalds’ cup and buried in the bin amongst crisp wrappers and old newspapers and someone’s hat.

“Is that so,” said her mum, not looking, frying fishfingers, a cigarette burning a brown stain into the ashtray beside the cooker.

Miss Jenkins had asked if Janet would like to come too, and Bridget, dealing with the shock of hearing a teacher say her mum’s name, she hadn’t realised Miss Jenkins even knew who her mum was, had replied that her mum wasn’t into it, which had made Miss Jenkins give Peggy Hilperton’s mum a look. The sun had filtered through the red thin strands of her hair and she’d gone off and written the note and come back with it and said, Be sure to get permission, mind. They’ll need to sign it.

“It won’t cost anything.”

“I can’t think they’ll be open on a Sunday, love.”

“Miss says they will.” She’d waited till Saturday teatime to ask. She’d spent all day doing errands for her mum; going down the shops for her newspaper, putting a wash on, hoovering the telly room, giving the bathroom a go where Paul had misfired on the toilet seat, cleaning up the cat mess behind the sofa, telling her mum to put her feet up, even rubbing her toes a bit.

Her mum took the fishfingers off. She stood at the back door exhaling smoke into the dark garden. “You’ll miss church.”

“God won’t mind.”

“And we’re set to visit your dad’s mum after.”

Bridget went to see her dad in the shed. He was counting supplies again. He’d filled in most of the checklist with big ticks, but he’d lost his temper when Paul hadn’t known the difference between the sirens and hadn’t had a clue what to do if he was caught outside or at school. Her mum had said, He’s only seven, Ray. Give the child a break. And her dad had turned red and said, You jump in a ditch, Paul. Can you remember that? You jump in a ditch.

Bridget hadn’t pointed out there were no ditches between St Biddulph’s Juniors and Hampton Close. Her mum had gone inside, and Paul had stood ashen, his bunny under his arm, and her dad had slammed the door on his shed as if they were all doomed since Paul was too little to remember anything.

“Can you sign this for school?”

Her dad took it from her hands, gave it a quick look, and stuffed it in the back pocket of his trousers.

“I could see Granny Reynolds next week instead.”

He focused his good eye on her. His bad eye, which lived behind a cloud, couldn’t focus on anything, but he focused his good eye and it was as if she could see all the possible outcomes of being in London when the sirens went off reflected in his lopsided glasses.

“I could hide in the gallery.”

“Whitehall will be the centre of their target.”

“I thought we were the centre.”

“We’re in the blast zone. They’ll be aiming right at you.”

“But not on Sunday. Not this Sunday. They’re not going to press the button this weekend.”

“It could happen anytime, Bridget. I’ve told you.” He tested a whistle.

“But you said Londoners would be safe because of the underground. I could hide in the tube station.”

He took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. “And spend the nuclear winter down there, is it? How do you propose to get home?”

“I’d walk.”

“And what about the weeks before when you’re not allowed out, before they give the all clear?”

“I’ll stay with all the others. I mean they must be stockpiling there too, you said so, that they’d be secret rooms in the tube stations where they’d be stockpiling. You said it stands to reason that the government would be building fallout shelters with all this stuff like they said you have to do, that they’d be doing it for all those people in London who live in flats and won’t have anywhere to go. I could be part of that. I could do all the stuff you’ve taught me. I mean you said most people aren’t preparing properly anyway, most people won’t have a clue so I can show them if I’m there.”

“I can’t have you going off to London, Bridge. It’s not safe.”

“London Bridge!” shouted Paul who’d crept up behind her when he saw her go in the shed. He started singing, London Bridge is falling down and blowing one of the whistles her dad had let him wear round his neck to stop his crying, and Bridget knew he’d be singing it all weekend if she didn’t do something.

“Where are you going,” said her dad.

“Help mum,” said Bridget, she went to her room instead.

Her satchel turned upside down and emptied of all the crap she kept in there. She pulled out the box her dad told her to keep under her bed. It had in it a torch and a sleeping bag and a bottle of water and a clock and a spare packet of batteries. She’d put some Tampax in there too but after she realised they were all going to die she’d started using them and now there was just an empty box to fool her dad if he ever looked. She put it all in her bag except the empty Tampax box, and then she went down to the kitchen and took a packet of biscuits out of the cupboard while her mum wasn’t looking.

Over tea Paul kept singing, London Bridge is falling down until she kicked him so hard under the table her dad threatened to make them both go and eat their tea in the other room.

She said goodnight and cleaned her teeth and pretended to get into her pyjamas only when she shut her door, she took them off and got dressed in her jeans again and slept in her clothes. She almost slept in her shoes but took them off at the last minute and left them by her bed. She left her curtains open and set her alarm and thought she’d never wake up if she slept, but did, suddenly, to the orange glow of winter lit by streetlights, the sun not yet risen. A fumble to silence her alarm, her beating heart to listen but the house remained perfectly still. She put on her shoes, put her school bag on her shoulder, grabbed her anorak from the hooks in the hall, and crept out of the house.

A short word in empathy for the Dad, who may appear foolish - and objectively is foolish - but: he's been brought up all his life to believe that the task of a man is to protect his family, just as the task of the state is to protect him in the completion of this fatherly function.

He is finding it simply impossible to acknowledge that in the face of nuclear apocalypse these tasks mean absolutely nothing. The absurdity therefore is not his personally but pertains to the whole situation of nuclear war, and is shared by all except those who act to stop it.

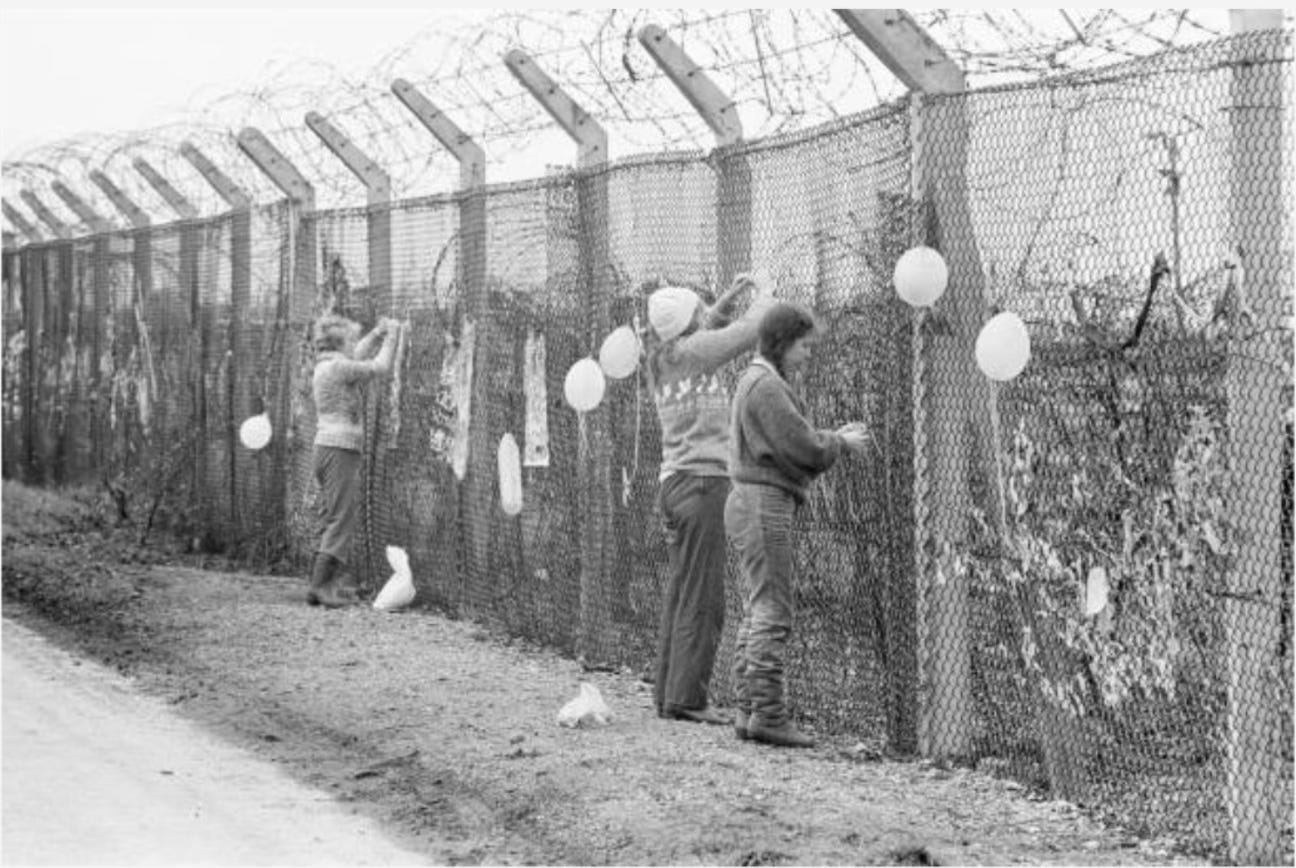

Go, Bridget! I love that in just 6 short chapters, we’ve already seen her awakening and taking decisive action. Having seen the context - her family, the era - I so admire her courage.