It was true, Kate was lonely. Wherever she went she felt like she was missing something, some part of her, whether in her kitchen or at the fence at Greenham a lack filled her as if a tide rushing into something stolen. You’ve so much energy, the other mothers from school would say to her as she organised the tombola, the nativity, the easter egg hunt. We don’t know how you do it! Said with an exclamation mark that made her afraid. Political acts of defiance filled the space inside her, surging on the heels of the void, she fought and she fought and she tried to give her life meaning. She said it was for the children until one of the terrifying women from the clearing asked her why she wasn’t doing it for herself. The question had floored her. She wanted to be something, she wanted to mean something, she’d found it at Greenham, almost, if she concentrated, if she didn’t let that sense of being nothing trip her up.

She idled at the roundabout at Yellow gate, her fingers tapping the steering wheel, her foot hovering over the clutch, the indicator on. Another car pulled up beside her, a man leered from the wheel, All right darlin? thrown through an open window and he was off ahead of her almost clipping the nose of a lorry indicating left. Even now, in 1983, men couldn’t resist a comment. She’d have thought the last sixty years hadn’t happened, that the suffragettes had achieved nothing but that piece of paper recognising them as individuals with a right to vote, the white ones, anyway; she’d had that pointed out early on round the fire at Greenham.

A Black woman in a frayed yellow jumper, a green stripe sprayed into her hair had said, “Not all women. Just the white ones,” and it had brought her up short.

She’d felt chastised and gone to the library and borrowed a book about Harriet Tubman. She’d tried to carry the conversation on next time she saw her but it hadn’t gone well. The woman had got up and left her mid-sentence. She was only complimenting her hair. But a single candle in a darkened world, that’s what some women had won, anyway, a single candle in a darkness that had persisted as if why couldn’t they be happy, these women; hadn’t they got what they wanted?

The strange, translucent Miss Jenkins sat statue-like beside her. Blood out of a stone. That’s what she’d been like this morning. Torturous. The thin white fingers of her left hand grasped the top of her tapestry satchel. Coaches were coming the other way as they pulled onto the road that circled the base, CND flags in windows and police disgorging from vans to wave them into parking spaces. A human chain link from RAF Greenham to RAF Burghfield via the research station at Aldermaston; they’d been told to bring scarves in case the chain had to be linked by wool. That’s where she’d met Simon, at Aldermaston on the 1963 CND march from there to Trafalgar Square, the last one they’d had, the one that had ended in a riot. He’d fallen in beside her, they’d walked the whole way together, three nights and four days and by the end he was holding her hand.

She’d drop off the costumes and get back to Yellow and find a place to hold hands with real activists as she had at Embrace the Base. She’d stand up for justice no matter what Simon said with his, Wife and mother threats. How dare he? When they’d met, before the girls, he’d been all for it. He'd gone on about the suffragettes as if he was one. When he’d proposed in a telephone box as they sheltered from a thunderstorm, he’d said, I promise to always let you be free. Let her. She should have spotted the farcical nature of his feminism back then when he was all, Isn’t my wife amazing? And, This is what a feminist looks like. He’d been right beside her, shoulder to shoulder when all she did was man the bloody stalls. He’d said he was so proud of how she set an example for the girls. But when she’d put the bolt cutter he’d given her in the boot of their car he’d taken it out again. He’d said it was only a joke. She had to think of the children. He’d said he was perfectly happy for her to make herself useful bringing supplies, even talking to the press, but Be sensible.

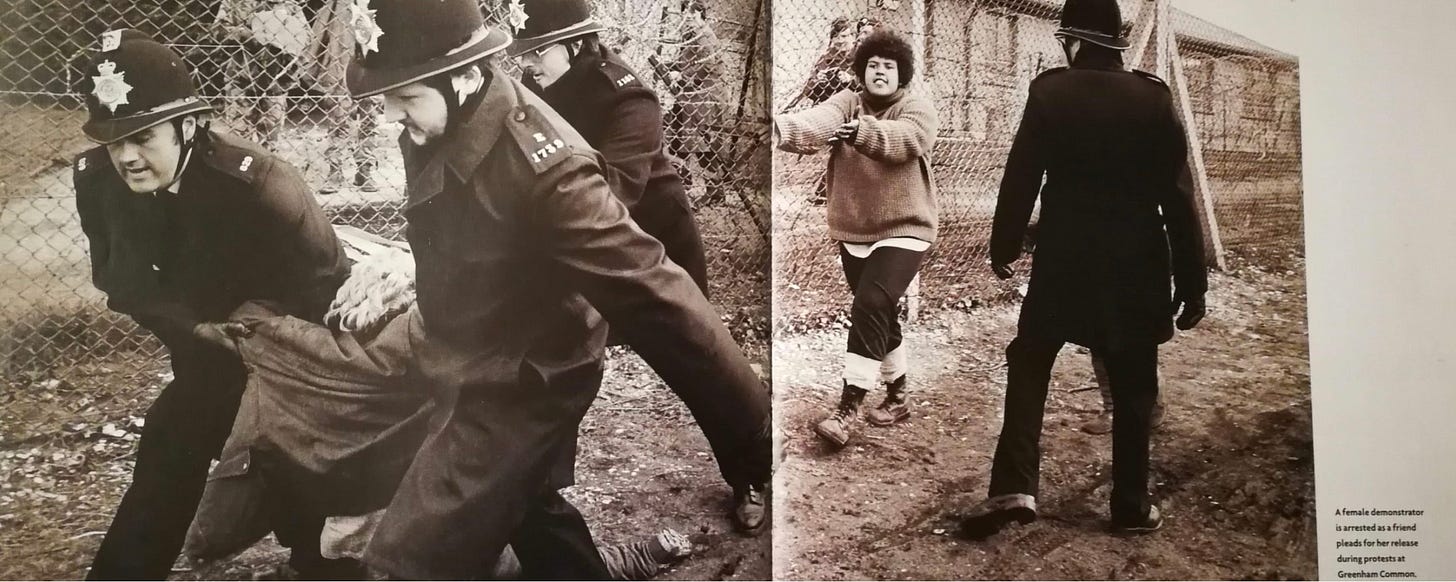

She’d joined the gathering outside of Newbury Magistrate’s court when the women from the silo action had been up in court. She’d given Irish Maureen a lift back to camp. She’d sat arm in arm on wet muddy ground, her back to the gates and had her body hauled aside, she’d gone door to door raising money for Greenham and she’d campaigned outside Westminster on Parliament Square, a banner pinned to the table saying Protest & Survive, the CND logo, leaflets for anyone who wanted them. What more could she do? Simon’s permission felt like a noose. He was, Happy to let her, he’d said last night after the children were in bed and the row that had been brewing over supper had made Joey and the twins refuse to eat their cauliflower cheese unless they were allowed ketchup like they had at school which Kate didn’t have.

“I’m happy to let you on condition that enough is enough. This has to be the end of it. I can’t be expected to bring up the girls on my own.”

Like I do? Kate had thought, watching him do up his pyjamas.

Her headscarf slipped. She parked up at Blue gate and retied it. She wasn’t going to let a tiff ruin her day. There were bigger things, more important things than a man embarrassed to tell his mother that his wife was off at, That camp again. Annabel was already out of the car by the time Kate got herself organised. She’d practically opened the door and jumped out before the engine was off. Kate was about to open the boot and retrieve the fun fur costumes when the shouting started.

“Bailiffs!”

Women running, grabbing everything.

I am in awe of how each chapter deepens and each character deepens. Seeing their outsides and then seeing their insides. And also 😡 at the pervasiveness of the word ‘let’. Even now.

“Let” indeed. A few years ago, I got this funny sticker, “Let women run shit,” but immediately realized - however well intentioned, the men who’d created it didn’t even recognize their assumption of control. It’s wild to be a gender your whole life and know in your bones people hate you for it.