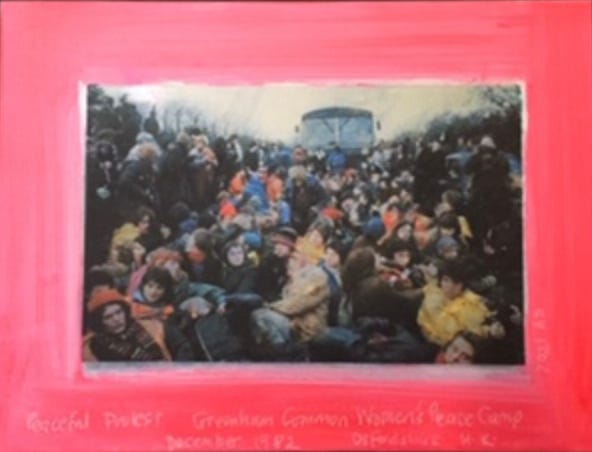

Kate turned to see a group of men coming over the rough ground like a fat, used army, answerable to no one but the council, no badges to identify, no numbers to report, three men ugly in their pursuit; they didn’t bother with munchers now they’d destroyed mostly everything. No structures were permanent anymore, they couldn’t be. The bedraggled mass of tents were tarpaulins put up in a day; long gone were the carefully built benders, the homes lovingly constructed.

She spotted Bridget tearing at a roof, all that hair that used to cover her face like a curtain now shaved into a mohawk mop held in place by dirt, revealing the energetic roundness of her that she wouldn’t thank anyone for noticing. A teenage girl no longer hiding; Kate could see it in the way she ran, she wasn’t thinking about her body, she was thinking about bailiffs and fences and fires. Kate had always wanted to take her aside, find the confidence in her, had watched her change from sweet little thing on the street to this lump that wouldn’t look up, and been swamped by the urge to rescue. It was Simon who’d talked her out of suggesting a women’s group. He’d said, Can you see Janet’s face? and Kate had had to be content with dropping hints about Peggy’s periods in the hope Janet would share something back.

Bridget tore past her with a sleeping bag bundled in her arms, one of a mass of women grabbing anything they could as the bailiffs moved through them, steady as an oil slick, catching their feet and stopping their rush with their arms. The fire was kicked out and pissed on. A barrel knocked to the ground, water pouring over tin plates and bowls that had fallen from a crate. She saw Maureen running to her little red car, a blond woman with spiked hair grabbing a shopping trolley piled with blankets, the Black woman with the yellow jumper frayed at the sleeves hurling insults while the fat man ignored her. Kate ran toward a man dragging what was left of someone’s home toward a pile they’d made, a pile that would be scooped up and dumped or left to be scattered by the wind and noticed by cameras, a mess the women would be blamed for.

“These are personal possessions, private property, you don’t have the right.” Her voice sounded thin in this open air, the squaddies watching from the fence, a thin line of police ambling slowly toward them, doing nothing. The man kicked over another barrel of water. Bridget ran past her, got lost in the woods, the same place as the others, all the women at Blue gate up and off, trained to survive this battery while the bailiffs destroyed their homes. The police watched on as another man approached Maureen’s car, Maureen in the front seat, the window up. Kate ran over.

The man knocked on the car window with his knuckle as if Maureen was broken down, as if he was there to help. “Come on my love.”

Maureen’s voice came muted through the glass. “Don’t you my love me.”

“Now, this is your car, is it? It’s parked up illegally on private property and I have orders to remove it.”

“You’re not taking my car.”

He was trying the door while keeping his eyes on her, his voice, level. “Your car has been impounded.”

“It’s my home.”

“It’s council property.”

“It’s her car,” said Kate.

The camp was ruined, a mess, empty, a smoking desolate ruin, a fence beyond, squaddies watching but out of the woods the women were emerging, their possessions hidden, they returned with free arms and they gathered about the little red car with Maureen in it. The blonde woman got on the roof. The Black woman got between the bailiff and the window, her body a shield to Maureen’s locked door. Bridget sat on the bonnet. Others pressed in behind the bailiff, his maleness amongst women a stark shock. The other two had gone off, women already running ahead of them to warn the next gate. The wind picked up and the smoke from the ruined fire blew across the car shielding Maureen more, her determined face, her hands clamped to the wheel as if she was driving.

“My love you need to open the door now,” his voice soft as if he was helping his aged mother, this kindly pretence, this man trying to rip a woman from her home.

“Leave her alone,” shouted Bridget.

The bailiff got his body against the car again, his fingers wrapped around the door handle as Kate had wrapped hers through the chain link fence, his efforts to remove a woman, hers to remove a bomb, the threat of war, an annihilation that would see this man melted along with the rest of them. The blindness, the conformity, the stupidity made her feel weak.

A tow truck reversed towards them, chains were being undone, a crowbar handed over.

“Now, come on my love, out you get.”

This time the door gave, it swung, and Maureen almost swung with it, one hand gripping the steering wheel, the other trying to pull the door shut. “I won’t.”

“Come on my dear,” his fingers around her arm.

A man in a suit pulling a woman from a car, a tow truck reversing toward them, women on the roof and the bonnet, pressing in, shouting, pulling, chanting, shielding with their bodies, cries of Leave her alone! as the campfire smouldered and the police watched smirking, doing nothing.

They pulled her from the car, two of them now, one of the men from the tow truck lending his weight to this woman whose home they were taking. The soft voice of the man in a suit calling her, Love as if helping his aged mother. They pulled her like meat that had got stuck in the grinder, tugging at bits of her, not caring if something broke. They left her immediately on the rough ground as soon as the last of her had left her home, her little red car, they waved their arms as if landing planes, as if some great work had been done and the tow truck reversed, and the chains were linked and the car was dragged as Maureen had been dragged and the man in the suit walked away.

They lit the fire again after the bailiffs had gone. They’d got good at lighting wet wood. Women emerged with the belongings they’d snatched up in time, a bucket, a kettle, some blankets, a tarpaulin tent.

“Who’s up for a fucking tea party,” said Maureen, her grey hair plastered almost over one eye, sweat smeared across her forehead. They rolled some logs for seats, a moment to gather themselves, all their armchairs smashed and torn apart, the rag taggle front room furniture ruined by men in suits with boots and no numbers.

“Did they get the costumes?” said Dawn.

They hadn’t touched Kate’s Volvo. It was still parked on the road where she’d left it.

Kate and Annabel laid fun fur out on tarpaulin. Dawn put her legs in a bear, Cerise and Kate took the unicorns with rainbow horns, Maureen went straight for the bright yellow cockerel, Annabel shook out the tiger, and Bridget looked out on her sixteenth birthday through the eyes of a giant pink bunny.

God the blindness depicted with such urgency. Brilliant juxtaposition between the men’s efforts to remove the women and the women’s efforts to stand fur saving life including the men.

"A teenage girl no longer hiding; Kate could see it in the way she ran." Bridget's transformation is almost complete. You've given us the perfect witness of that in Kate. Masterfully done in the brilliant mayhem of the scene.