The only way to think about her life now, was Before and After Greenham. Before she’d been a stupid girl in Surbiton with embarrassing parents. After, and that was after her dad was led away by Maureen, she was a grown up, or nearly, or not a kid anymore anyway. For a start she’d taken off her bra. And she’d made friends. That first night at Greenham, after her dad had been led away, she’d wrapped her sleeping bag around her shoulders and sat by the fire with Cerise.

Not a single person told her to clean her teeth or be polite or she might look better with a fringe. Maureen took the armchair that was the colour of Miss Jenkins’ corduroy skirts. Miss Jenkins and Kate sat beside each other on the other side of the fire, far enough away for Bridget to pretend she didn’t know them. She could see Peggy smoking a cigarette.

“We’re all of us running from something, love,” Maureen said to Bridget, even though Bridget hadn’t said anything. “My daughter-in law thinks I’m on a painting holiday in the Lakes.”

“Doesn’t your husband mind?”

“He’s dead love, two years ago. They wanted me to sit tight and knit my own coffin, you know?” She kicked a log into the fire.

“But you ran away?”

“I do what I like,” said Maureen.

“This is anarchy,” said Cerise. “I run away from fucking Spain.”

“My nanna and grandad live Spain.”

Cerise spat on the ground. “My grandpapa was murdered by Franco.”

“Shit,” said Bridget. “Was he a mate or something?”

Bridget got an entire history of the Spanish civil war round the fire that night on her first night at Greenham, a history interspersed with the story of a man who’d told Cerise he loved her, then hit her, then married her, then hit her again until she’d run away, sold her violin, come to Greenham, come out at Greenham, awakened from the slumber of her heterosexual life. It had taken until they were in the bender again about to go to sleep, the candle blown out, for Bridget to ask what anarchy was.

“No leaders. I govern myself. I am free to do what I want, and you are free to do what you want, and as long as I cause no harm it is okay. Okay? People think anarchy is chaos, but it’s not. It’s self-governing order. It’s the best of human nature.”

“What about having to do things, though?” Bridget thought of the tea she’d drunk and the sandwich she’d eaten, the bowl of stew she’d been handed while Cerise explained Franco. Who had made those? She hadn’t. She hadn’t washed up, either. She lay on her back in their tarpaulin tent in the woods that dripped with firelight and stars.

“We organise,” replied Cerise, doing the same, their heads almost touching. “We communicate. If we want something, we do it. You want a fire tomorrow? You want to be warm? So we get wood. No one is telling us. Our bodies are telling us.”

Bridget imagined the whole of England collapsing in on itself if there was no one telling anyone what to do.

Cerise continued, “I have this conversation, people think everything would stop and that would be bad. I tell you what would stop, this fucking system, this system built by men in power, the capitalist prison. The people would organise, look how we organise here, look how we build systems. No one is telling us. You are in charge of you, I am in charge of me. That’s it.”

“I’m an anarchist,” said Bridget, pulling her sleeping bag up to her chin and imagining how her mum would cope if Crossroads wasn’t on.

She slept deeply and soundly and woke with only a flash of wondering where she was. It was like family camping only much, much better. No Paul in a sleeping bag next to her. No dad shouting at mum for forgetting the tin opener. It hadn’t occurred to her before now that that’s why they went there, to the crappy camp site near RAF Molesworth. He’d always been mad about the army. He’d jumped on Protect & Survive as if it made him part of it.

When morning came she crawled out of her sleeping bag and found breakfast round the fire as crowds of women gathered at the gates. She went to the art tent and finished her banner, with Cerise’s help she hung it on the fence, a magnificent display that was all hers; she’d never felt so proud in her life. Her glorious artwork, a tree and a missile and a message from her to join the messages of others that turned this fence into the best shout she’d ever seen.

She joined the blockade, one among thousands strung between webs of wool from chain link to tree to boot to arm, an armour of woollen thread, they sat where they stood, thousands of women singing songs they all knew, that Bridget learned, that she heard over and over until the words spilled out of her mouth too, side by side with people she didn’t know, their arms linked, bodies in the mud and refused to move even when huge trucks arrived with men poking their heads out and guns strapped to their sides.

The police hauled them away to let the trucks through and Bridget tried to do as Peggy had taught her, go limp, let them drag her, resist by no resistance but she panicked as the black clothed arms came nearer, as women on either side were pulled away, and she scrambled up and hopped over arms and legs to find another place further back, where there were still a wall of bodies between her and that army of uniform moving women like rag dolls, tossing them aside into brambles. She saw Peggy and her mum later on by the fire. They told her she had to go home with them. Miss Jenkins found her too, looking not much like Miss Jenkins at all with her hair tied out of the way. They all said she wasn’t to run off again. But she did.

Hidden in the woods, the art tent, Cerise’s bender, day turned to night turned to day, and she found herself alone and not alone, a happy new morning making porridge with Maureen, the sun pushing through cloud, the camp waking up and settling down, chatter and cigarettes and no sign of Miss Jenkins or Peggy or Peggy’s mum this time. Maureen put a paper bag on her head and sat in the tatty red armchair by the fire. The porridge looked disgusting.

“It’s not for eating,” said Maureen.

“I know that,” said Bridget, though she didn’t.

“You flick it, see?” She took a spoonful to the fence and flicked a great slop at a military convoy idling at the gates. It splattered the windscreen and the driver set the wipers on it, spreading it neatly over glass. “Not too bright, are they?” Maureen gave Bridget the spoon.

A happy morning spattering army trucks with porridge, Bridget had never had so much fun in her life, she couldn’t believe she was allowed to do it and laughed so much she nearly peed. A Black woman called Dawn joined in. She wore a torn yellow jumper frayed at the sleeve and had a green stripe sprayed into her hair. They got it everywhere, down their sleeves, all over their clothes. Afterwards Bridget ran her head under the standpipe, freezing water dripped down her neck and when she looked up she saw her mum.

Her dad must have driven her. Her mum didn’t drive. But he wasn’t beside her or loitering in the background, she couldn’t see the car. Her mum looked like she’d watched Bridget do a double somersault or something, she was that shocked, her mouth open, her hands by her side. She was in her other coat, the one she used for camping when it didn’t matter if it got messed.

Dawn handed Bridget a towel, Bridget rubbed her hair with it, her head pleasingly numb with cold, when she shook it, she felt icy drops flick all over her face.

“The state of you,” said her mum.

“What?” She didn’t care.

“What have they done to you?”

She went to hand the towel to Dawn, but Dawn had gone over to the fire.

“They haven’t done anything to me.”

“You’re to come home.”

“Where’s dad?”

“He said he’d stop at a cafe. He said to call him from a box when I found you.” She pulled a scrap of paper out of her pocket; a tissue came with it and fell on the ground.

“You’re to come home, Bridge.”

“I’m not coming home.”

Her mum started to cry.

"Bridget imagined the whole of England collapsing in on itself if there was no one telling anyone what to do." A great line!

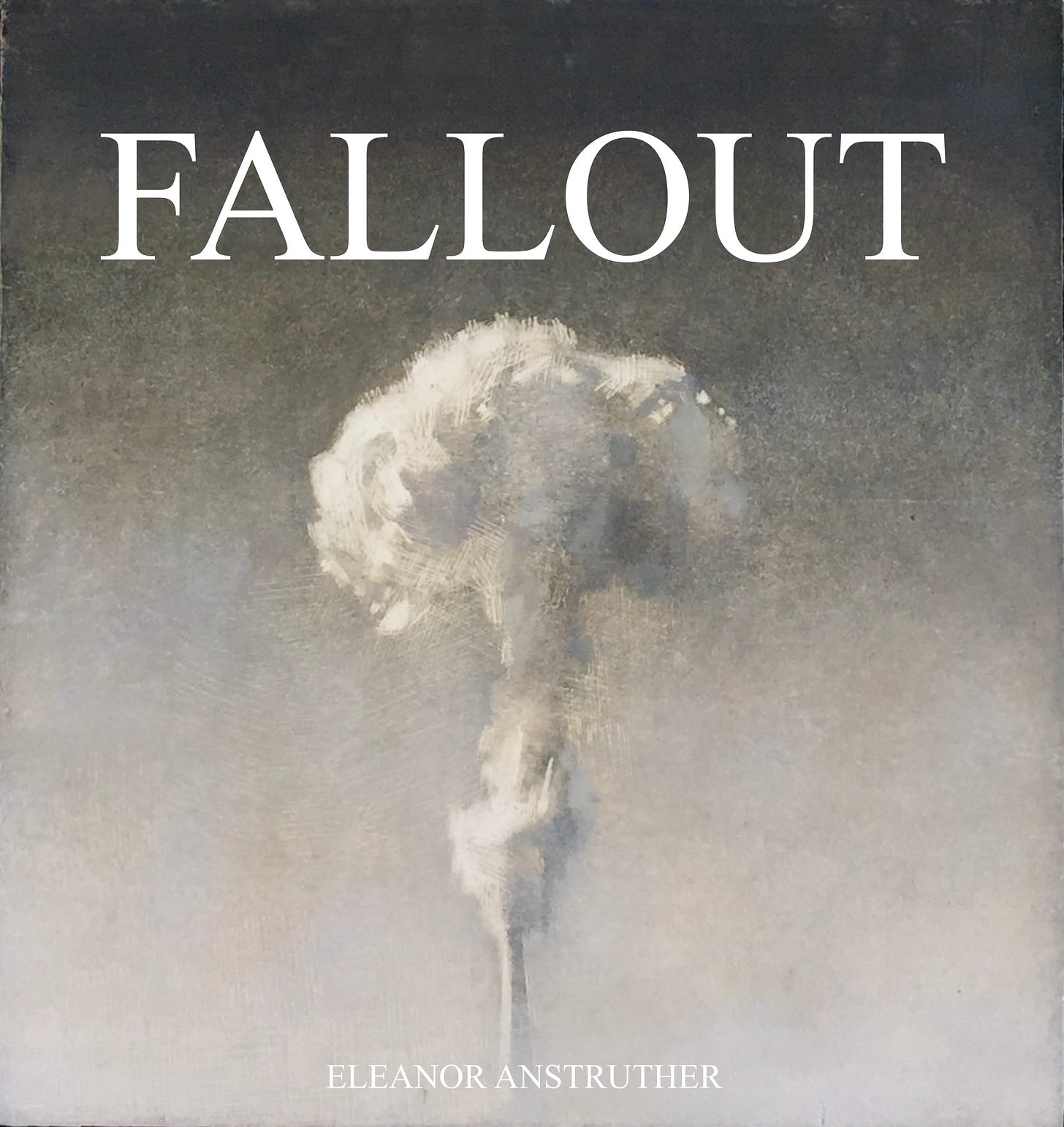

Fallout is many things. And one of those, the coming of age piece, especially speaks to me in this piece. My heart opens to Bridget and to Cerise and Maureen and Bridget’s mom and all of them and all of us and the different ways we learned and didn’t to care for ourselves, to be ourselves, to make stands when stands need making, to connect and separate ourselves from systems that don’t nourish us all at once. In other words, your deft storytelling has me thinking and feeling much.