They poured out of the coaches and stood on the grass and Bridget looked up and down the line and at the makeshift camp and the tents and Portakabin and at the tens of thousands of women and couldn’t believe it. There was a hush as if they were seeing stars and God and magic, a hush against that chain link barbed wire fence that protected the bombs that were built to kill them. She’d got there by running away. It had been the red leaflet shoved through the letterbox that she’d watched her mum crumple that had done it.

*

“What is it?” Breakfast time. School. Bridget in her uniform. Her dad reading the paper, her mum in her school tabard even though she wasn’t due in till later. They’d all heard the letterbox snap; seen her little brother run out at the sound of it, his pink rabbit under his arm. Paul had a thing about the post. He liked to hand it out. Only the post had already come, and this wasn’t a letter for any of them.

“Green Ham.” A red leaflet in his small hands, folded in the middle, unfolded by him. Their mum took it off him. He reached for it back. “What’s Green Ham?”

“Green eggs and ham,” said their dad without looking up from the paper. “It’s an American thing. Let me see.” He knew a lot about America. He’d been there once.

Their mum crumpled it and stuffed it in her pocket. “It’s a load of nonsense.” Crumpled in her hand, crunched into a ball, shoved into the wide floral front pocket deep with lint and tissues and Rothmans cigarettes and a lighter, her soft fingers always worrying the things in there, fishing them out, a tissue for a nose, things absently shoved. Bridget had said a million times, Can’t you look normal? But her mum said she had the same job at home as she did at school, so she may as well wear the uniform.

“Let me see it.” Ray held out his hand. His glasses were crooked, they always were, and smudged and half off as if he couldn’t stop adjusting them. They were part of his face like his eyebrows and nose. He couldn’t see a thing without them, not out of his bad eye anyway, the cloudy eye. He kept pairs all over the place, always losing them.

“It’s nothing.” Janet got up and tidied the counter where toast crumbs littered. Paul sidled up beside her, his pink rabbit swapped to his other arm. Bridget could read his mind. Little snake. Smiling up at their mum while reaching into that soft front pocket and grabbing it.

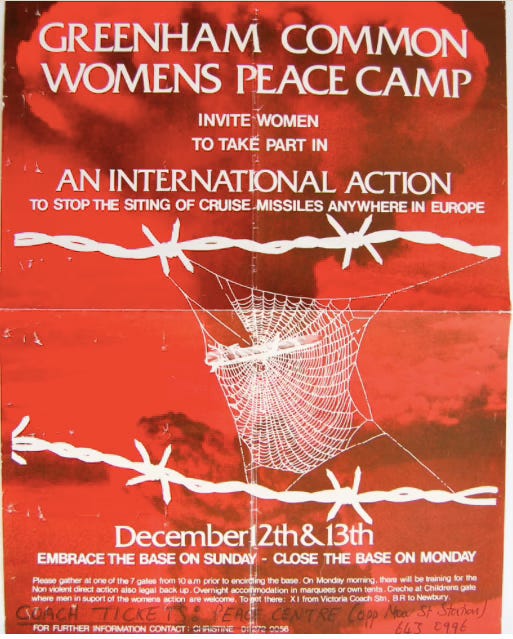

“Oi.” She wasn’t quick enough. He skipped around the table waving it in the air. Barbed wire streaked across blood.

“Paul you little shit.” Bridget was up out of her chair after him.

“Language.” Both their parents together but this time her dad grabbed Paul with one hand and the leaflet with the other and straightened one his knee and let the other go. He adjusted his glasses and read aloud, “Greenham Common Womens Peace Camp. They’ve missed off the apostrophe.”

“Trust men to miss the point,” said Janet smiling at Bridget.

Bridget came round to her dad’s side and read over his shoulder, her palm shoved into Paul’s forehead to keep him away. “An international action. For what?”

“Embrace the base on Sunday, close the base on Monday.” He shook his head and left the table, tapping the leaflet twice as he went.

“Where you off to?” Their mum was a good foot shorter than their dad, and a good deal younger.

“Get my map.”

Bridget sat in her dad’s chair. Paul bumped against her arm; she grabbed his rabbit and held it over her head, making him squeal and run to their mum, making her say absently, “Now give it back,” while clearing up the breakfast things. Bridget chucked it at him. She flattened the leaflet on the table like her dad had done. Between the two strands of barbed wire was a web that held something long and wrapped. The wire and the web lay across an image she’d seen plenty of in her dad’s newspaper, that mushroom cloud that her dad said the Russians were threatening them all with and only Maggie and Ronnie could keep them from being blown sky high. Only he called them The Ruskies. And he said, Maggie and Ronnie as if he knew the prime minster of Great Britain and the President of America personally.

“It’ll be that Mrs Hilperton,” he said, returning with his map, and clearing a space on the table. Paul’s bowl of Cocopops nearly hit the floor. Janet caught it with both hands. She patted her lap, calling Paul to her, and fed him the rest of his breakfast like a dog, he stood beside her with one hand on her thigh, his mouth opening and shutting to her spoonful’s. The cat sat at his feet. Bridget watched her dad turn the pages of his Big Map, standing over the table like a commander, leaning on one arm, his fingers spread while with the other hand he slowly turned the pages. His Big Map wasn’t like the fold out maps he kept in the glove of the Vauxhall Rover, this one never left the house and was kept in the telly room in the cabinet so it didn’t get marked. He used it to prepare the fold out maps to the correct bit so that when they went on long trips like to the campsite which they went to every year, all his planning would work as long as their mum unfolded the fold out maps in the order he’d told her to.

He traced a road with his finger.

“Peggy Hilperton’s mum?” Asked Bridget. Peggy wore bovver boots and had a satchel covered in badges. They were in the same year at school. They’d never so much as looked at each other.

“They’ll be sorry when it’s them left out in the cold,” said Ray.

Janet put Paul’s bowl in the sink and took the leaflet out of Bridget’s hands.

In the hall, satchel on, ready for school, her mum tried to do up her anorak even though she was fifteen. Bridget shoved her off. The cat came racing out of the kitchen followed by Paul who bashed against Bridget on purpose as he made the turn around the stair post and raced up the stairs behind the cat he’d named Kitten.

“Get your brother down those stairs.” Her mum said everything quietly. Bridget wished she would shout sometimes or do something mad, but her mum swished along in a haze of cigarette smoke and gentleness as if she lived in a cloud; nothing touched her. The rest of them, Paul, Bridget, their dad moved with the jagged sense of a world outside; Paul raced and Bridget slumped and their dad bent but Janet floated above it. When they went to Eden Walk shopping centre in Kingston, she’d choose a bench and send Bridget and Paul off to wander about, saying she was quite happy sitting there. It made Bridget want to fight.

“You get him,” said Bridget, with her eyes locked on her mum, and as Janet turned to call to Paul, Bridget reached into the soft front pocket of her mum’s school tabard, grabbed the leaflet and shot out the door.

You do a great job of showing us in a few paragraphs the dynamics of this nuclear family. (There. I've gotten that terrible pun out of my system).

With so words, you firmly establish the setting for the story and the personality of this family. I’m excited to be here from the beginning and to see how it unfolds week after week.