Ray and Annabel careered along the A339, following signs to Newbury. Already squashed together for the best part of an hour, Ray had smoked the entire way. Annabel was convinced she was suffocating. The passenger window didn’t work, and Ray refused to open his side.

“She’ll be perfectly safe.” She’d said it at least twice.

“I’ll be the judge of that.” He’d refused to let her hold the map. He tore the page turning it over and almost set the car alight trying to light one cigarette off another. Basingstoke was badly scalded and he was going to have a job finding Reading.

They approached the last roundabout at speed. Annabel hung onto the sun visor with one hand, her seatbelt with the other. He swung the car round and slammed on the brakes as they came suddenly upon the queue of parked coaches lining the road.

Annabel ricocheted off the glovebox. “You can park there,” she struggled with the door handle. Never in her life had cold air felt more alluring. She rested a moment, dizzy against the car.

“Right,” Ray tried to do up his coat, the zip ran without effect. “Where is she?”

They faced an encampment of darkness and firelight, silhouettes of heads back lit by military haze, bodies everywhere, heads and shoulders moving in clumps, singing amongst trees and laughter in the night; she could be anywhere. Since the sun had gone down the gathering had gathered closer.

“You’d better wait here.” She’d tried to explain in the car that he wouldn’t be allowed in after dark.

“I will do no such thing.” Zip zinging up and down, but he didn’t move away from the Vauxhall.

“I’ll do a search and come back.”

“I’m not falling for that, Miss Jenkins. Fool me once, fool me twice.”

“Mr Reynolds, I keep telling you.”

But he set off at a fast lurch as if only that pace would propel him free of the safety of the Vauxhall Rover and into the crowd. Annabel trailed after and saw him arrive at the fire to a wave of protest. Chairs were knocked over.

“He’s with me,” she cried, picking up her pace.

“Get him out of here.”

“I did try to tell him.”

“You have to go.”

“He’s lost his daughter.”

A large woman faced him down, three others corralled him.

“Who’s in charge?” Said Ray.

“No one’s in charge,” said an elderly woman.

“I want to speak to whoever’s in charge.”

“Why do men always think someone has to be in charge?”

“I want to speak to the head of this, of this,” and he waved his arm, unable to find the words.

“No one’s in charge,” said the elderly woman again.

“Please, Mr Reynolds, if you’ll only wait in the car,” said Annabel.

Bridget watched from the door of the bender, on her belly, her lower half warm in the sleeping bag. When the one headlight had swung across her face she’d known it was her dad, even before she heard his voice, who else would it be, who else had one headlight working and never got round to fixing it? From where she lay the figures around the fire were black lumps with the occasional dim lit face flickered over by light, but she knew his slim shoulders, his tall skinny frame, she knew from the commotion and women standing like lions surrounding him. She could hear shouting.

Cerise wiggled round in her sleeping bag, she stuck her head out the door.

“My dad,” said Bridget.

“You should go.”

“I’m not leaving.”

“You don’t have to leave.”

“I’m not leaving,” said Bridget again.

Her dad was trying to break free of the crowd. There were arms waving and voices raised, a patrol of squaddies leaned on their side of the fence, their nightly entertainment, one of them shouted, “Man overboard!” and another, “Go on, lad, swim for your life!” as Cerise put on her boots.

Bridget heard him say, “I’ll call the police.”

And someone shout, “You won’t have to call far.”

She pushed her way to his side, “I’m here, dad. I’m here.” He almost squeezed her half to death but she said, “I’m not coming home.”

“Yes, you are, my girl.” He wouldn’t let her go.

“No, I’m not.” She pulled away, bumping against shawls and woollen coats. “You can’t make me.”

“You can’t make her,” said a voice in the crowd.

“Your mother’s worried sick.”

“No, she’s not,” she pushed him off again. “She only worries about Pauly and you and what’s for tea and sending me down the shops. She doesn’t do anything. The world’s going to end and all she cares about is Crossroads and whether I’ve done my homework. I’m not coming home.”

He rubbed his bad eye in the way he did when he didn’t have any answers, like when she asked him how they were supposed to get the stuff from the shed and not die from atomic dust, or the time she’d seen him in eye shadow and lipstick and the next day at breakfast said, I saw you come in, and he’d ignored it, ignored her, gone off to his shed.

He rubbed his eye and lied to her. “I didn’t say we were all going to die.”

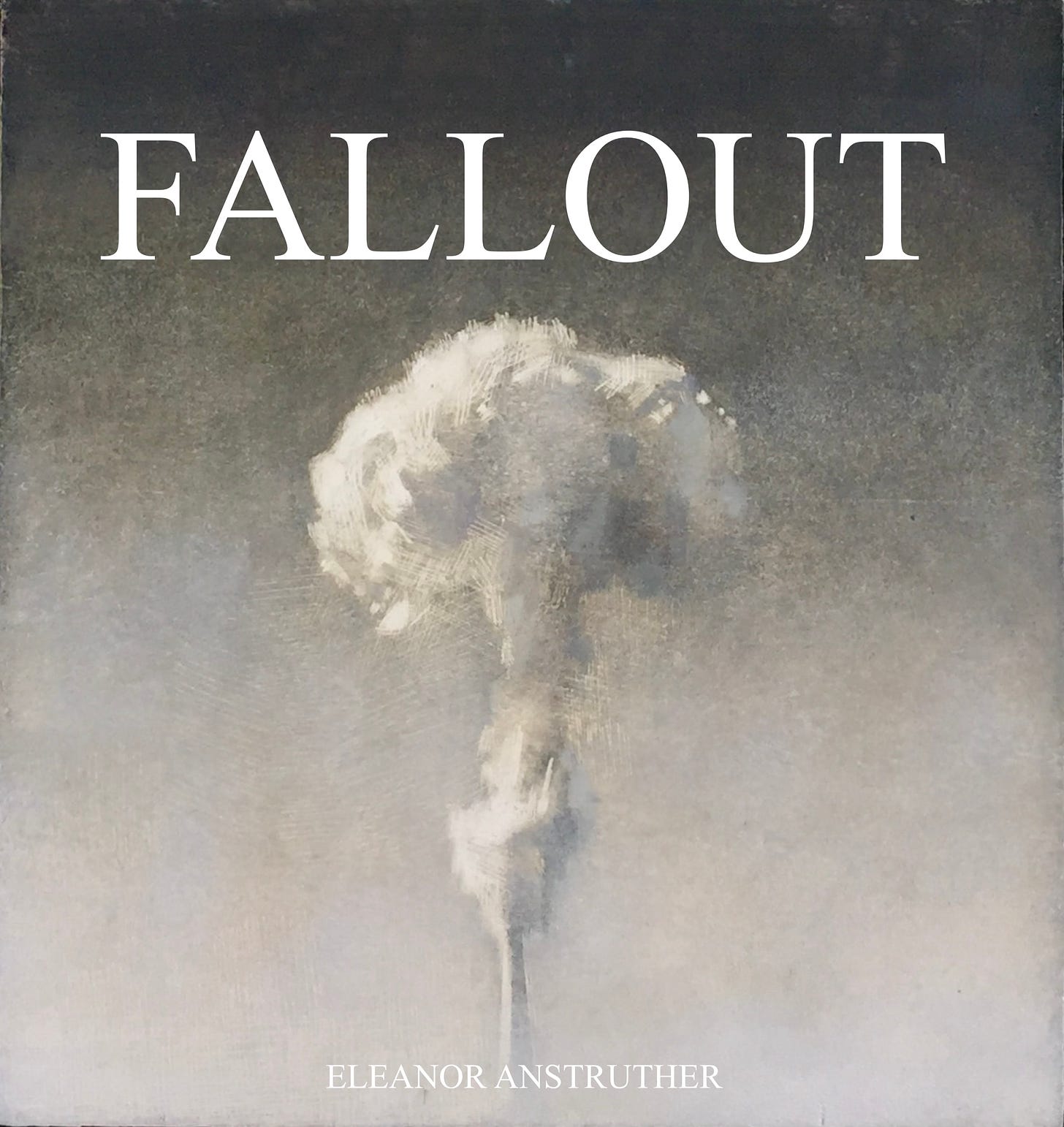

“Yes you did. You said all our fool neighbours would be for it, while we’d be stuck in your fallout shelter, only you and I both know that’s not going to save a fly. There’s going to be a bomb, that’s what you said.”

“I said to be prepared.”

“A few blankets and four million rolls of toilet paper aren’t going to save us. I’m not going to die in Surbiton, dad. If they’re going to bomb us, I’m going to die here.” A cheer went up that took Bridget by surprise. She’d never thought anyone took notice of a single thing that came out of her mouth. The women behind her were clapping. “At least I can be who I want to be.”

“We’ll keep her safe,” said Kate, who’d seen Ray Reynold’s arrival at the fire with shock, followed by relief, followed by panic.

“She’ll only miss one day of school,” said Annabel.

“Why don’t we get him a nice cup of tea,” said the elderly woman who’d taken his arm quietly, without him noticing, who was already leading him gently away.

“What’ll I tell your mother?” he threw the question over his shoulder at Bridget.

Bridget shrugged. She was already bored with the conversation. “Tell her she should come too.”

There was no way she was only staying one night.

*

Ray let himself be led away. It was one thing to curse the lesbians while he was safely in his chair and they were safely on the TV, but this was like an episode of Cagney & Lacey only there were about ten Cagney’s and fifteen Lacey’s and as far as he was concerned, one of each was pushing it. That art teacher twitching away beside him all the bloody way up the M3, that women’s lib Kate Hilperton jumping up out of nowhere, he’d have words with her husband when he got home; he didn’t know what words, but as he was led away to his car, he was sure they’d come to him.

He turned down the offer of tea.

He got in the driving seat of his old Vauxhall Rover, started the engine, his one headlight lighting up a policeman in the passenger seat of a van parked across the road who turned and looked at Ray, opened his door, got out and walked over.

Ray wound down his window.

The policeman leaned in. “You want to get that fixed.”

“Will do, officer.” Ray lit a cigarette.

“You one of them husbands of this lot?”

“God no.”

The policeman leaned closer. “If I had my way, I’d drag the lot out and shoot them.”

“Too right.”

“They want getting rid of.”

Ray exhaled. “I’m with you, officer.”

“Send in the firing squad. That’d teach them.”

“Too right,” said Ray.

“Still,” the policeman straightened, “the law’s the law. You’ll get that headlight fixed now, won’t you, Sir?” He tapped the roof of Ray’s car, two short smacks that said, Men are men.

Ray was glad for the dark and cigarette smoke, the engine and mud, the wheels of the Vauxhall spinning and turning, the rules of a knowing look, man to man with nothing else to be added, a shorthand for understanding, a cover to cover up what couldn’t be said, the accelerator lurching him safely away into the night.

This novel is amazing on so many levels, Eleanor. Story, character, prose and it’s a masterclass in multiple points of view.

the grating of a zipper trying to pull things back together, how they "should be" - sliding, in charge, but without purchase, then resigning to things left open, in frustration. still, the law's the law. amazing Chapter, Eleanor. you can feel Bridget's empowerment and determination, and the futility of authority lashing out, in a space it doesn't fully control.