Everyone at CND and at school said they didn’t know how Kate did it. Five girls under sixteen, how did she manage to do anything besides laundry, cooking, shopping, cleaning, starting all over again? She’d say what a helpful mother-in-law she had, and how she couldn’t do it without Simon, and they’d look flabbergasted when she told them how he shared the washing up. The other mums would say, Imagine my Gary going anywhere near a sink! and laugh, and Kate would feel excluded instead of proud. And she’d want to say as she manned the anti-apartheid table or the amnesty international table or canvassed for the Labour Party or handed out leaflets for Greenham, How can you stand it? But the other mums, who passed by her table with their strollers, with their children pulling on their arms, looked at her with pity as they headed off to the cake stand, and instead she’d hide the photographs of beatings and bombs under her palm and say, Please come, we’ve meetings every month, in the cheeriest voice she could muster while knowing they wouldn’t, and half wishing she could hide her morals as easily and join them for a slice of Victoria sponge.

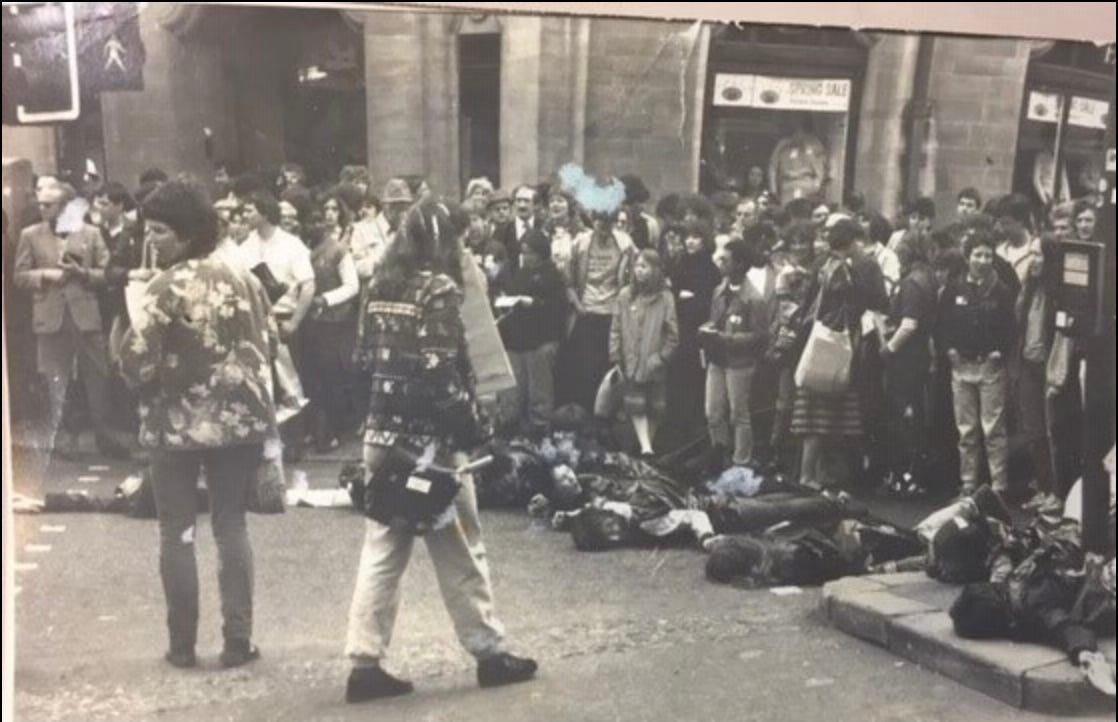

Up until the summer of that year, that’s all she’d done; man the stalls. She tried to inject the phrase, Woman the stalls, but it hadn’t stuck, and so she’d manned the stalls and handed out leaflets, and watched the other mothers pass by. She was ravaged by the pain of injustice, the stupidity of government, yet a sense of helplessness fitted in between sweeping up Lego with the bulldozer of her hand, had kept her bogged, had kept her doing little else until the sinking of The Belgrano. Up until that massacre, she hadn’t put her body in the way.

“And now the bloody Maggie and Ronnie show,” she’d fumed at Simon.

Supper in the Hilperton household. Simon had made nutloaf.

“They’re calling it a Die-In.” She dished out salad.

At the torpedoing of an Argentinian war ship, as Thatcher celebrated the death of three hundred and twenty-three men, Kate’s local CND had announced an action led by Greenham women, to lie in the roads when President Ronald Reagan came over.

“Like Lady Di?” said Petra who’d been obsessed with the royal wedding to the point that Kate had felt ashamed.

“No. Not like Princess Diana. Amy. Hands.”

Her littlest girl pulled a chair to the sink. Simon turned on the tap.

Their kitchen was twice the size of the Reynold’s next door, she’d seen theirs, Janet Reynold’s husband Ray had sold them number five, and when Kate had knocked on the dividing wall between the kitchen and front room he’d entered into a long conversation with Simon about supporting walls. But Kate had insisted they wanted it open plan, insisted Ray Reynolds look at her even as they’d sat in the Reynold’s front room being served half a lager, and a gin and tonic for Kate, even as Janet Reynold’s wouldn’t catch Kate’s eye either, the smoke from her cigarette curling in the stifling air, as her husband had said, Why would you want to sit with all that cooking going on? And laughed as if Simon would get the joke.

A dark front room for men, guests, and family television in the evening, when what Kate wanted was light, and inclusivity, and to get as far away from the nineteen fifties as she could. Peggy was already peeping out from behind her skirts, Kate was already pregnant with the twins, and they’d bought number five, saying cheerily on the doorstep how the girls, Peggy and Bridget, would be friends, how they must come round, and knocked the dividing wall down and opened up the kitchen to fit the table Simon bought from a car boot sale off the A3. A decade later it was covered in children’s drawings, the table scarred with crayons and spills, and they’d put the television in their bedroom.

“Won’t you get your head run over?” Robin was the elder of the twins by twenty-six agonising minutes.

“We’re representing the dead in a nuclear war.” Kate sat down, picked up her fork.

“On a weekday?” Simon dried Amy’s hands and lifted her from sink to table.

“Don’t lie in the road, Mummy.”

The twins were identical, white-blonde, she’d tied ribbons to their wrists when they were younger so as to tell them apart.

“They’ll stop the cars,” she squeezed Robin’s hand and moved her plate closer in the hope there wouldn’t be the same scene as the last time Simon cooked. How were men to learn if women didn’t let them try? She’d pretended his vegetarian chili con carne was delicious and she’d do the same tonight if she had to. The children looked at her with pain. Simon asked his mother to do the school pick up. Kate took the bus into the city and put her body in the way of capitalism.

It had switched her on as if sixteen years of childbearing had put her spirit on pause. It had lit her up. She’d lain in the road in the city of London with men like Simon, only not like Simon at all, stepping over her and walking round her, men on foot getting irritated and men in cars blaring their horns. Kate and the Greenham women with her were the bodies of war, the exploded and slowly failing, the cancerous and fallen where they stood. It had fouled up the working day. It had made a point. Kate had gone as a mother and come back an activist, the activist she’d been before Simon, before Peggy. Raising conscious girls and having a husband who shared the cooking were suddenly no longer enough.

At the campfire, Kate found a chair, a view of the fence, somewhere in the throng of silhouettes at the fence was her Peggy, shouting for every woman in their ancestral line who’d been shut up, bound and gagged, told to get back to the kitchen. She was so proud of her. When their copy of Protect & Survive had clanged through the letterbox, ordered by Simon, Peggy had thrown it across the room and shouted, We’re all fucked. Kate had been so angry she’d threatened to chain herself to the railings of Downing Street. Simon had read, When The Wind Blows to the twins at bedtime and given them nightmares.

Kate searched the faces around her, the wrapped in scarves, the hats pulled low, but even in that disguise of winter she could see that none of them were Bridget.

"But the other mums, who passed by her table with their strollers, with their children pulling on their arms, looked at her with pity as they headed off to the cake stand, and instead she’d hide the photographs of beatings and bombs under her palm and say, Please come, we’ve meetings every month, in the cheeriest voice she could muster while knowing they wouldn’t, and half wishing she could hide her morals as easily and join them for a slice of Victoria sponge." The perfect bathetic touch of the Victoria sponge—just lovely.

I admire the way you captured the subtle, dismissive disdain Kate felt from the other more “traditional” mothers. And her brief pull to fit in and be accepted. As social creatures, we are wired to seek belonging. It’s no wonder we sort ourselves into tribes. Kate and Simon are such compelling characters.