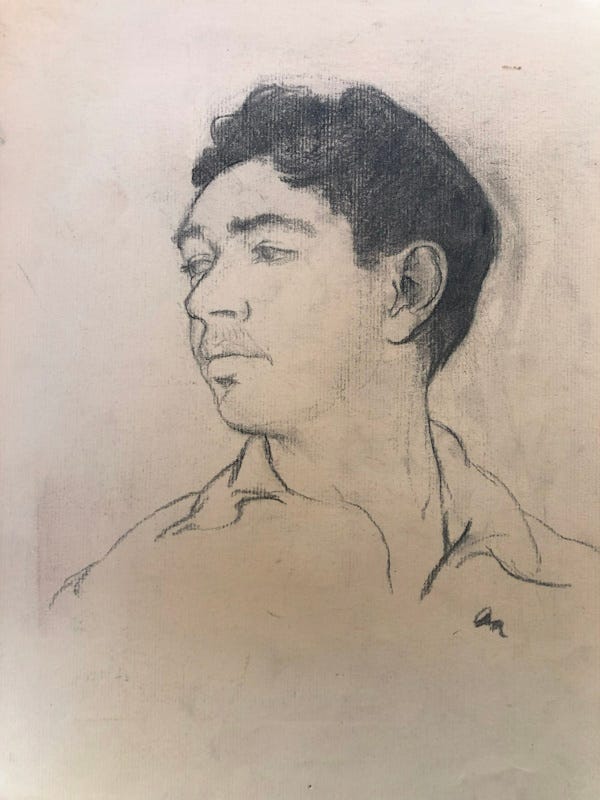

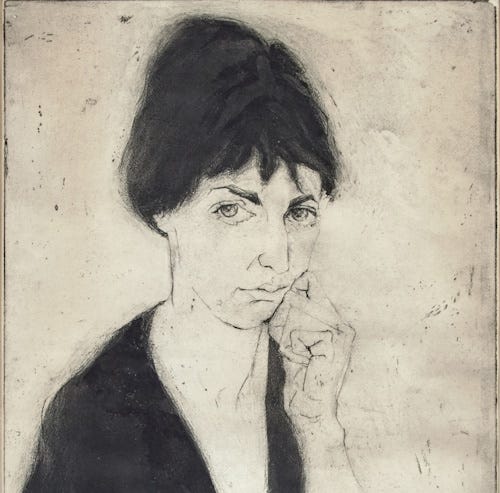

writes Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents.: stories from life with her long-divorced parents, the artists Lennart Anderson and Mimi Weisbord. Her father was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters; her mother was a comparative unknown who became an outspoken New York feminist in the 70s. When Mimi died during the pandemic, Eliza began excavating the SoHo loft where her mother lived and painted for 40 years. Digging there helped answer questions she’s long held about what drew her parents together on the Lower East Side in the 50s and blew them apart in Park Slope in the 70s. Mimi would often tell people, “Stay out of my studio!” Now, it’s Eliza’s to share with you.

1. Why Substack?

I needed a way to clean my office. While drafting my memoir about life with my late parents, I’d clogged it with drawings, paintings, letters, photos, show announcements, and news clippings from my mother’s loft in SoHo. I have empty file cabinet drawers ready to help me sort the detritus. But when I touch these things, they tend to tell more stories. I thought if I had a way to get down those stories, I’d feel motivated to attack and sort the piles. I’m also building a platform for Two Houses, A Memoir of Art and Divorce (in progress), and Substack is an excellent way to keep me writing while finding a community of writers and readers. But alas, those piles remain.

2. How long did it take you to find your groove?

I don't know if I have! Right away, however, I felt rewarded. I had started with a WordPress blog but felt I was writing into a void. On Substack, I decided to sign up everyone I could think of and let them opt out as desired. I even posted on FaceBook that subscribing them was a birthday present I was extracting from friends and family. In this way, I began with close to 150 readers. Over the last 15 months, just a handful have unsubscribed, while Substack has brought me hundreds more. That approach was pretty audacious, but from what I can tell, writers must endlessly self-promote. Ironically, that does not come naturally to me. Maybe because I grew up in the shadow of big artist egos?

3. How has it changed you?

Substack has been a profound experience for a host of reasons. Two Houses. Two Painters. Two Parents. shines a bright light on the dark crevasse where I’d lived between my parents, a place that was neither his nor hers and entirely hidden from view. Their divorce cut me in two because I loved them both, and they wanted nothing to do with each other.

I go between my parents as I would two worlds. I have two identities. They do not talk to each other; they do not know who I am with the other.

– Eliza Anderson, Two Houses, A Memoir of Art and Divorce

Writing here, I stitch myself whole; I put their lives and paintings side by side in front of a readership that includes people from their lives and art careers. This is a completely out-of-bounds act in the logic of my divorced family and my parents’ professional lives. It feels wildly transgressive. But many knew my mother as just a nude or head on my father’s canvases; now readers can see from my point of view and understand that Lennart Anderson began his career married to another emerging artist. My post “Woman in Black” is about discovering my mother’s early success.

4. What mistakes have you made?

I don’t know yet. But I have made social faux pas. Before I understood this platform, I embarrassed myself with Margaret Atwood. In my mother’s loft, I found evidence that my mother knew Atwood in the early 70s when my mother was producing women’s poetry programs for WBAI-FM. Of course, I wanted to know more and reach Atwood, so I subscribed to her substack and left a comment unrelated to her post (before DM was available). I said something to the effect that I doubted she was reading post comments herself and that it was unlikely she’d even see my message, but I explained who I was and some of what I’d found in my mother’s loft. Well, she replied pretty quickly, with nostalgia for that era, confirming she knew and remembered my mother. I was over the moon excited but also deeply embarrassed. I had no idea the platform was an authentic way of communicating with authors. I’m now enthralled with this aspect of Substack.

5. To pay or not to pay?

My posts are free, but last month, I turned on the option for readers to pay for a subscription. I have been afraid that if I had paid subscribers, I’d feel anxious, which would get in the way of what I’m doing here. I’ve felt the need to be sure I can write from my own center of gravity. When I got my first paid subscription, it was thrilling to feel that kind of support. At this stage, financial support seems to provide the kind of ego boost that fuels rather than hinders writing freely.

6. What artistic and technical choices have you made?

I write bits of memoir, from short meditations to long-form essays. I often include voice-over, occasionally embed video clips and photographs, and I always explore ways to use and respond to my parents' art. When I began writing after my mother died, I didn’t dare include their art at first. My parents were always very sensitive about their work, as all artists are. It took a long time to dismantle the “hands-off” feeling. Now, I love that Substack offers a way to showcase them while enabling me to emerge as my own artist. It’s also been fascinating to see my parents differently through the excavation of memory, art, and stuff. There are ways that their work maintained a dialogue with each other despite their walled-off lives. I’m still exploring that. An example is the essay I posted after the election: “Hundreds of Drawings Turn Up by My Father, Lennart Anderson”

7. What’s been the effect on your writing?

Substack provides an occasion to write and to keep taking risks. I’m always thinking about how to work differently with my material. Having a ready audience plays a big part in that engine. However, the dopamine hit of self-publishing and immediate reader feedback is intoxicating and a bit dangerous. I fear letting pieces go too soon. Still, the comments I receive are often so insightful — a big motivator to keep developing as a writer. Many of my readers are very accomplished writers and artists; I even toy with soliciting critical feedback.

People who knew my parents also email me about my posts. Very old friends of my mother recently found me on Substack, which led to intense sharing. And I found Victoria Olsen here, writing about her artist father, Earle Olsen, a painter who knew my father. We’ve since made a profound connection. After learning about Earle, I considered the risks male artists took to follow their passions in the 50s and wrote “Wounds of Our Fathers.” Substack is an incredible space for me.

8. In it for the long haul?

It felt impossible to write about my parents until after they were dead, and now that I’ve survived them, I’m eager to learn where the writing and Substack will take me. Themes of art, divorce, feminism, grief, and Time resonate with many writers and readers on this platform; I cannot imagine giving up the community I have here. The post I’m currently working on hits this niche squarely: “Tips for Divorced Artists Raising Children (Buckle Up).”

I’m also thrilled to have readers in different countries. I plan to meet up with Gregory Garretson in Lisbon this month. He’s the linguist who writes Living Elsewhere. We’ve been recommending each other’s work, and he’s been growing my list, especially since one of his posts went viral. His parents split when he was little, too, so I feel like I’ve found my people, but I look forward to finding more. I’m a daughter of divorce and also a daughter of second-wave feminism whose mother was full of contradictions and died with searing dementia. That’s a special place in hell that I expect to further explore.

Subscribe to

I really enjoy Eliza's writing here (we connected over clearing our parents' houses). Thank you for featuring her, Eleanor.

A compelling marriage of art and reflection. Thank you, Eliza and Eleanor.