Janet had had enough. She’d had enough of waiting for her daughter to come home, the terrible imaginings, the impotence of Surbiton and she’d had enough of her husband leaving at all hours as if it was all right for him to disappear without a word, not bothering to lie anymore, just whistling out the door regular as clockwork, every Saturday night, never bothering to tell her where, never offering to take her with him or take her out at all, coming home with lipstick in the cracks of his mouth. It was one thing to make them all practice for the nuclear holocaust, it was quite another to wear red satin knickers with a white lace trim under your pyjamas and think your wife wouldn’t notice.

She used to blame Bridget when her things went missing, not that the knickers were hers, she’d never wear anything so flashy, not as a married woman, who was going to see anyway, not Ray who hadn’t seen her in her smalls since Paul was conceived and even then, he’d probably had the lights off, he’d probably told her to undress herself. Not the knickers, but other things; a mascara she’d bought specially for the school Christmas party, a lip gloss the lady in Boots had said would make her look kissable, any number of bottles of toner and cleanser and make up remover. Only that afternoon a new pair of tights from her drawer had gone missing; she’d laddered a pair on the corner of the oven door as Kit had skittered under it chased by Paul and she’d been turning the fish fingers over and had to scoot round to stop him landing in the oven with them. She’d snagged her leg on the broken corner that Ray never got round to fixing, he said it wasn’t a new door they needed it was a whole bloody oven. She’d gone up to check she had a fresh pair, or would she have to get down the shops on Tuesday after the weekend and easter bank holiday, she was sure she’d bought two packets of dernier ten and lo and behold, none, just the pair of fishnets she’d worn once for Ray and never tried on again. She wanted to say to him, Ray, love, why don’t you tell me? But she’d come downstairs, and he was in that shed again and then he’d gone out and she was left alone with only Paul for company.

He wasn’t a bad father; Bridget and Paul adored him, or Bridget used to till she got her period and her spots and chub and went off him like she went off everything except food. He was a good man in lots of ways. He never hit them, he wasn’t a drinker, he hardly ever raised his voice. He brought home the bacon as her mother would say, his work colleagues seemed to like him, he’d been at Seymours long enough, a steady hand, good at shifting the duds, that’s what they’d told her when a few of them had come round for a whisky after one of the old buggers in the office had died. When Bridget was small he’d sing her Vera Lyn songs to help her get to sleep and make her cry with laughter doing Elvis impressions off the telly, shaking his hips about and letting his hair flop forward. She’d thought he was a bit sad, that was all, when she’d met him, a lot of these older men had stories from the war they didn’t talk about, he hardly spoke about his past, just that he was a chauffeur to some family in Hampshire and he hadn’t fought because of his eye. She’d thought she could fix him up with a good meal and some love, bring out the best in him. Sixteen years later and she wasn’t sure if all she’d brought out in him was a liking for frilly knickers.

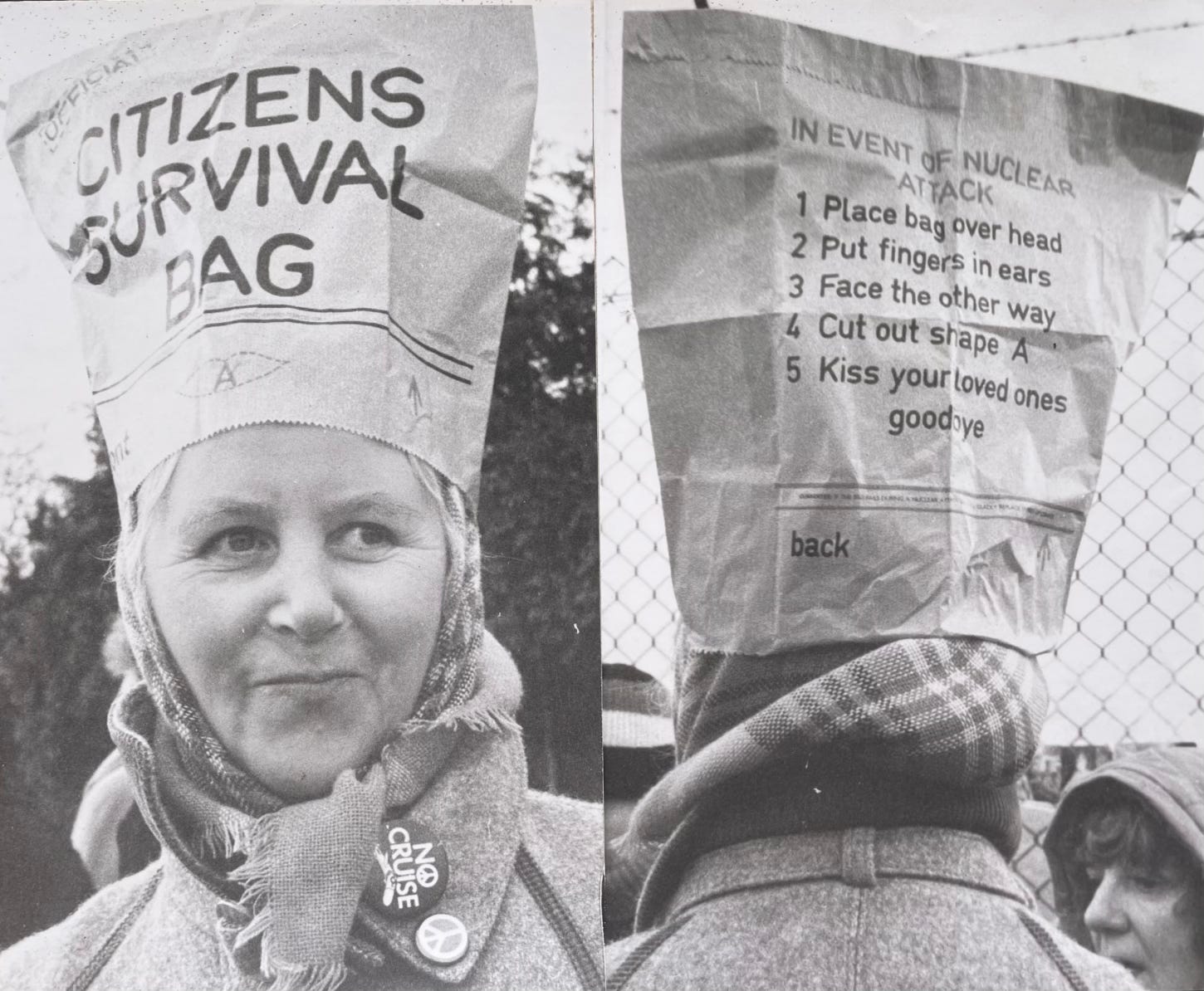

While Bridget was there it hadn’t mattered so much, so he had secrets, so what, look at the fella at number three who if he wasn’t a kiddy-fiddler Janet would eat her hat, and Ray wasn’t doing anything so evil as that; it wasn’t as if he was doing any harm, all humans had funny ways, look at Danny Le Rue. No one turned a hair when he paraded about, fancying himself in earrings. A bit of harmless fun. He even got paid for it. If that’s what got her Ray going then so be it; there was a while when Janet had thought they might even be friends, her and Ray, if only he’d let her in. Give them something else to talk about other than his bloody fallout shelter and frightening Pauly half to death with his talk of acid rain and how he’d have to get used to doing his business in a bucket. If only he’d confide in her they could go about together, it would be their little secret, not his. Knowing him and his funny eye he’d be getting his make-up all over the place. She could have given him tips. It could be a laugh. No one could say she wasn’t open minded. But since Bridget had gone she’d lost her ally and what was odd had become lonely.

She was sick of being taken for a fool. She stared at the darkened ceiling, unable to sleep. God knows where he was parading. She’d got tickets to Danny Le Rue once, but Ray had gone on about what a sight he looked, and it wasn’t decent, and couldn’t Janet see that man was making a fool out of all of them, all those women who cheered as he hoisted his fake tits about and winked at the camera. Rich coming from you, she’d wanted to say but hadn’t. He ought to trust her. She missed her daughter so much she thought her heart might break.

This time she was going to say something. This time, after church, tomorrow lunchtime before he made any excuse to go off, wiping his mouth and leaving the clearing up to her, she was going to sit him down and have it out. For all she knew he was coming home at lunchtime and trying on her clothes. What if he got caught? What if he lost his job? Then where would they be? It wasn’t good for Pauly, and it wasn’t good for her; as for Bridget, the girl wouldn’t notice if a fly landed on her nose, but it wasn’t good for the family, she’d come home one day, she couldn’t stay in that camp forever. Janet lay in the dark, eyes open, staring at the ceiling and heard the thunderclap and the rain pour down, alone in the marital bed on a Saturday night, she couldn’t see what time it was, but it was late, gone three, even Ray should have been back by now.

He wasn’t back when she made egg and soldiers for Paul sleepy in his dressing gown, rabbit tucked under his arm, kicking his legs at the kitchen table. He wasn’t back when she put on her best coat and dragged Paul to church with the promise of stopping at the Hilperton’s easter egg hunt after. On her knees in a pew she prayed God would forgive her for giving him what for when she saw him again, she prayed in advance of her anger.

At the Hilperton’s the door was ajar, Janet stepped gingerly into their hall, she could hear the party in the garden. Kate threw up her arms with a small, unnecessary scream when she saw her, and hugged her awkwardly, Paul pulling on Janet’s arm, Janet standing as still as possible. She only let her go to introduce her to her mother.

Janet directed Paul’s face towards the old woman seated at the long wooden table. “Paul, say hello to Mrs Hilperton.” Paul skipped from one leg to another, face craned to the action outside.

“Maureen isn’t my mother,” said Kate.

She let Paul go. He burst from her grip at a run. “We’re not stopping long but I promised him eggs. You know what they’re like.” Maybe this grey-haired woman in Kate’s kitchen didn’t know what they were like. Maybe she’d be putting her foot in it all afternoon.

“Mine are all grown of course,” said Maureen.

Kate topped up Maureen’s glass.

“I think I’ll go outside,” said Janet, still in her coat. “He’s got his dad’s stomach.” It was only just gone twelve. She hadn’t eaten since a bit of toast before church. She had sausages waiting at home though God knows Paul was going to be full of chocolate. She tried to see him in the rush of small heads tearing about with baskets in their hands.

“Ray not with you?”

“He’s having a lie-in.”

“Janet’s Bridget’s mum.”

“She’s a good girl,” said Maureen raising her glass.

“Have we met?” said Janet.

“But since Bridget had gone she’d lost her ally and what was odd had become lonely. “ Such a great line, this idea that all of Janet’s justifications work up to a certain point, but eventually lays bare the loneliness underneath.

The loneliness. So beautiful… all the ulterior feelings that make people do what they do.