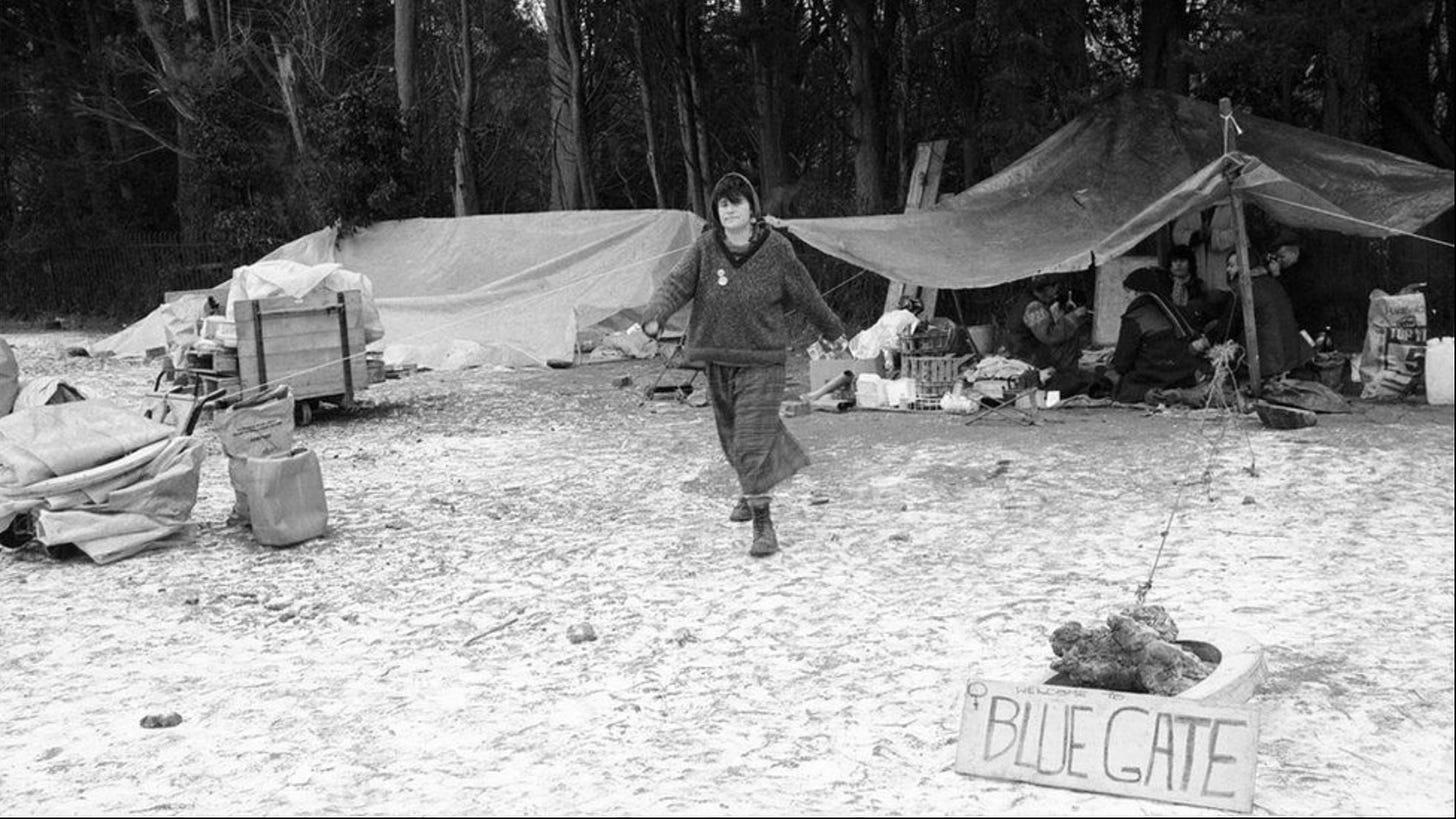

Bridget was woken by Cerise singing happy birthday in Spanish, and bringing her a tin mug of lukewarm tea, the milk curdled as usual. She’d told Dawn and Cerise and Maureen over a shared pint at the Rokeby Arms that April Fool’s would be her sixteenth. She’d be legal. She could cross the fence. They’d taken the piss like everyone did, her birthday was a joke, yeah, yeah, but this time she didn’t care. They were planning an action, and she was going with them.

It began like all the actions at Blue gate, with Dawn saying, Wouldn’t it be funny if.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if we broke in dressed up as animals?”

“We could do it for April 1st,” said Maureen.

“That’s my birthday,” said Bridget.

She told them how at school even the thick kids, who didn’t know what day of the week it was, would snigger and Bridget would wish she’d never been born. How her dad used to say, Stop being so silly. No one will laugh when she refused to wear her birthday badge. How they did. Every time.

Dawn and Cerise and Maureen raised the shared pint to her and told her about the CND action planned for that day, the human chain link from Greenham to Burghfield via Aldermaston. How boring it sounded. That wasn’t what they were going to do. They were going on a Teddy Bear’s Picnic.

So Bridget woke on her sixteenth birthday not nervous of going to school like every other year, not dreading her mum saying, Wouldn’t you like a few friends round, love? But with butterflies in her stomach of excitement and planning and this was it. No more watching the others crawl through holes she’d cut in the chain link, no more waiting for them back at camp, seeing them return laughing, covered in bramble scratches, hearing about how they’d let the tyres down on a truck or sprayed, Greenham Common is common land on the side of the mess hall in massive red letters.

Cerise passed her a joint. “Your present.”

Bridget stuffed it down the end of her sleeping bag, she could have it later as long as she wasn’t arrested. Dawn had been on night watch, she crawled in for a few hours kip as Bridget crawled out. The camp was waking up; the fire stoked, the kettle was on, someone was shouting for water. Maureen loaded up the boot of her car with the empty barrels. Bridget jumped in the front seat as Maureen started the engine.

They drove round to Yellow gate, hauled the barrels to the standpipe, and filled them one by one. Water splashed over Bridget’s hands, soaking her sleeves; most of the time she was wet and cold, covered in mud, and hungry but she couldn’t care less, as long as she could stay. As long as she was free. She’d learnt not to complain. Maureen wore her paper hat, the, Citizen’s survival bag turned upside down that sent the journalists mad, the press who hung around Yellow gate loved her craggy old face, that stupid bag on her head. Maureen refused to give interviews. Her daughter-in- law had caught sight of her picture in the Irish Times and sent her son over with instructions to bring her home. They couldn’t have her, making a scene. Maureen had said, I love you, son, but you can fuck off and sent him packing back to Yellow gate where he’d parked his car, afraid for his mother, not understanding he should be afraid for himself.

Bridget breathed in the camp at Yellow gate, better chairs round the fire, they even had a sofa, and the kitchen tent was twice the size. They had bins that weren’t overflowing. All the donations came there. Squaddies leaned against the gate posts, police loitered nearby. She saw Kate Hilperton stand up and come towards her, a package in her hands, that concerned look that always made Bridget want to walk a mile in the other direction.

“Bridget, Bridget?”

Red package, cats on it. She recognised the wrapping from Paul’s birthday last year.

“Happy Birthday! I hope you don’t mind. I brought this from your mum. She couldn’t get away so I said I’d do it. She sends her love.” Kate held the present out.

Her mum would never say, Send my love. She probably said, She’ll never want it.

After she’d left her in Maureen’s car, after the bailiffs had come and wrecked everything and she hadn’t been able to call her, hadn’t been able to run to the phone box in town and ring home, say, Mum? because how would that look? she’d told Dawn she could never go home. Dawn had said, What’s he done, then, your dad? Bridget had let Dawn think it was something bad like the pervs they saw on TV who murdered children, she hadn’t been able to put into words the truth and the why, that he lied, that it hurt her, that his whole life was a front, his bloody fallout shelter, a cover for another bomb that he didn’t even have the words for, and nor did she.

“Won’t you take it?” Kate was still holding the present out.

Some of the women from the clearing helped them carry the full barrels into Maureen’s boot, the kind of women Bridget had never seen before she came to Greenham, who seemed half man half woman, who looked and spoke as if they weren’t either. Before Greenham, Bridget hadn’t known there were different kinds of women. She’d only known girls and teenagers and wives and mothers and grandmothers and they were all the same only older each time. These women with their short hair and boots and arms around each other who looked at Bridget like, Yeah? when she’d first arrived, the expression on her face must have been that rude, they lived their life how they wanted, they didn’t ask permission of anyone. They were like a species that had no interest in explaining how they’d got there. Bridget wanted to know where they’d been when they were her age, at school, where had they hidden, why couldn’t she see any in the streets of Surbiton or the playground of St Biddulph’s, but she was too afraid to ask.

Kate shoved the present through the window of Maureen’s car. “What shall I tell her? Shall I say you said hi, or thanks? Do you want to open it now so I can tell her? I could -” The last of Kate’s sentence was lost as Maureen put the car into gear.

“Aren’t you going to open it, then?” said Maureen.

Bridget threw it in the back.

At Blue gate they hauled the barrels out and someone made tea. After she’d warmed her hands and dried her sleeves, she fetched the present from the footwell behind the driving seat. The paper was wet, one side had collapsed. There was a bit of red knit revealed, it had to be a scarf, her mum would have stood in the shop worrying about whether she was keeping warm as if she was still a kid who didn’t know how to dress, thinking, as she took it to the till, how well it would go with her white jumper with the red flowers on, as if she was still stupid enough to wear matching colours, clothes for church, outfits her mum thought looked nice. As if her stupid red flowery white jumper wasn’t scrunched in a bin liner in her dad’s stupid WW3 HQ and probably stinking of damp by now and eaten by moths.

Bridget scrunched it up and shoved it down the bottom of her sleeping bag with the joint. Her mum could fuck off. If she really cared, she’d stop trying to make her go home. She’d stop being such a fucking doormat and stand up to the patriarchy. She’d come to Greenham and protest with her.

Because I’m a husband and father I find myself extra curious about poor Ray. He seems so fragile and pathetic, like Willy Loman. Given the description of his workday––rain soaked and raving about bomb shelters––I get the impression he’s not closing many deals. That leaves Janet to be the earner, the opposite situation from Simon and Kate. Janet’s emerging for me as the person most affected by Greenham.

By god, I love these characters—all of them so brilliantly painted.