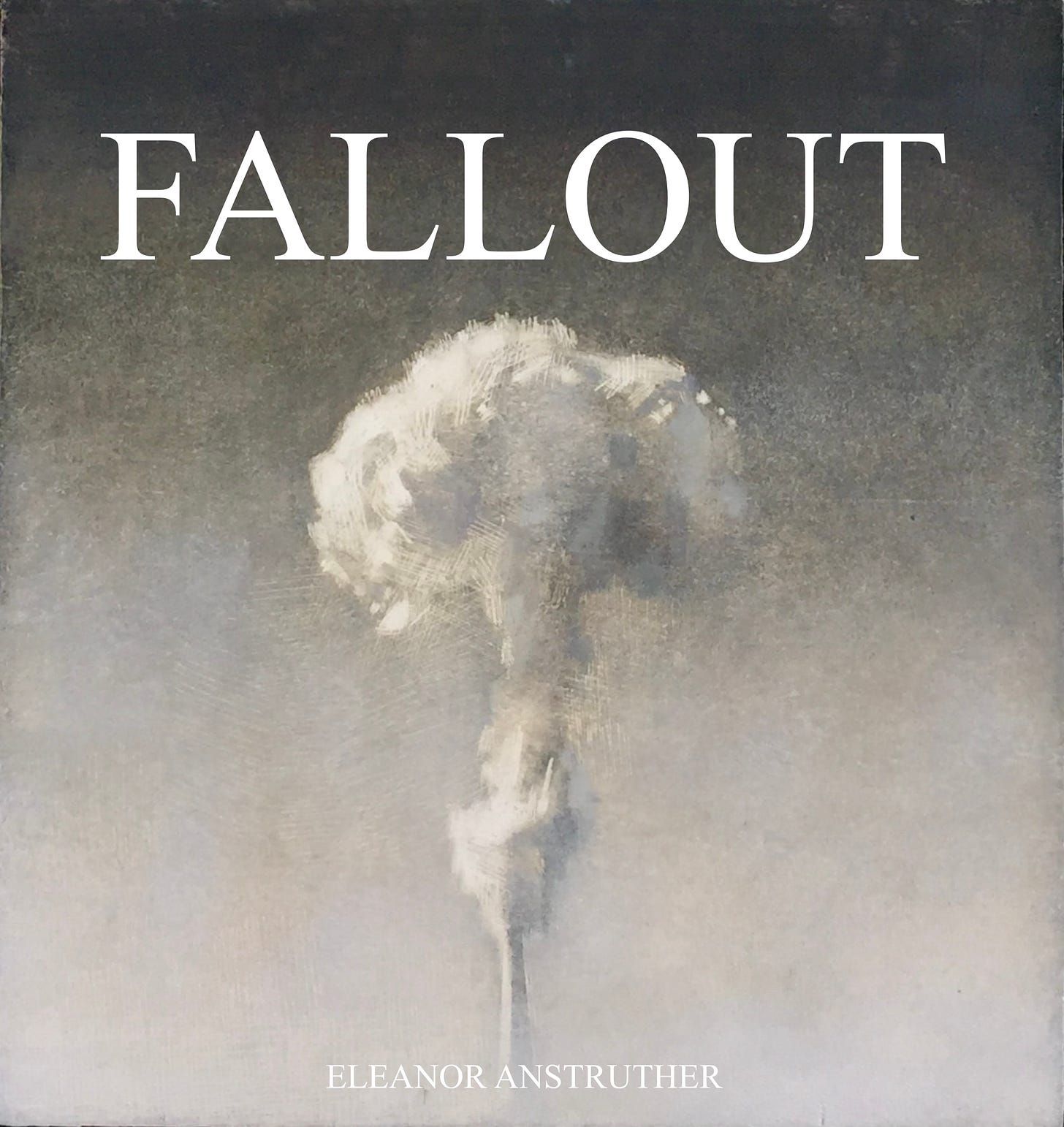

By breaktime she’d coloured in all ten, and two of her own design. Miss Jenkins had painted a watercolour of hills with a black cigar shape at the front and a white dove coming off it and underneath she’d written, Greenham Women For Peace. Bridget had stuck with the red, she liked its bold bloodness, she liked the barbed wire, how it made her think of catching her thigh and her skin tearing, blood spilled onto dirt. On one of hers she’d drawn a mushroom cloud going up behind a tiny house, people running, her mum and dad and Paul and Kit the cat. On another she’d trapped a body in a spiders web of wire, hands gripping, mouth open like the Pope, a scream muted. She imagined a breeze making it sway like the high ropes at Center Parcs where she’d gone with her dad when Paul was a baby and they’d left him at home with her mum. That had been when her body was a vehicle for getting around and not an enemy, and that had been when her dad was fun. Ever since secondary school her body had betrayed her, and ever since Protect & Survive arrived her dad been weird. It was like the bomb and her body had got in cahoots to ruin her life.

Her dad had brought home all the Protect & Survive booklets from work, too, as if one wasn’t enough. He said it was no good leaving them out, it put people off viewings, as if what was the point of buying a house if World War Three was coming, as if it was especially pointless buying a flat or a bungalow; the booklet said as much. Her dad said the ones he really felt sorry for was if you lived in a caravan. He said the advice for them was to Ask their local authority what to do. As if there’d be time for that. As if they’d care, her mum had added in a rare moment of protest. Her mum usually said, What’s that got to do with me? when her dad went on about politics. She liked to say, Leave it to the politicians.

“Where are you going to put the writing?” said Miss Jenkins.

“What writing?”

“You’ve got to tell people where to go.” She pointed at the other leaflets.

Bridget had felt tip and crayon all over her hands, the tips of her fingers were pleasingly blushed. “What people.”

“The people you’re giving the leaflets too. Come on Bridget. This isn’t just for fun.”

Bridget rubbed the mouth of her figure, smudging it darker red. She was only asking questions to keep Miss Jenkins talking, it didn’t matter what. Once she got going she’d forget that Bridget was supposed to be somewhere else. Sometimes Bridget’s friends, if she had any, which she didn’t, but the girls that she sat with sometimes, they’d get Miss Jenkins on to the subject of Women in art and she’d get so wound up that they’d miss half of their next lesson.

“What’s it for then?”

“Bridget,” said Miss Jenkins. “You can’t tell me you don’t care about the bomb.”

Bridget could tell her a lot of things, how her mum and dad expected her to tell the truth even though they didn’t, how stupid they were, how her dad was old and her mum pathetic, but she couldn’t tell her she cared about the bomb because she didn’t. So what if the world ended. What did she care. “My dad says I’m to come home when the sirens go off.”

Miss Jenkins put down her paintbrush. She’d painted tiny delicate white letters on the black cigar.

Bridget carried on, “He makes us practice having tinned tea once a week. He tried to make us eat in the downstairs toilet till mum said enough was enough. She said it’ll be bad enough doing it for real, no need to practice thank you very much.”

Miss Jenkins picked up her paintbrush again. The tip hovered over the missile.

After the Protect & Survive booklet turned up her dad had said they couldn’t use the downstairs toilet anymore because that was going to be their fallout room.

Bridget had said “How are we all going to fit in there?”

He’d told her not to pick holes and knocked a hole through to the under the stairs cupboard. He’d said Paul would have to go at the end.

She’d imagined cramming in as the sirens wailed. She’d imagined them all standing like sardines in the dark while the whole world fell down around them.

She’d said, “Can we fit Uncle Bill?” She liked her mum’s brother but her dad had said Uncle Bill would have to fend for himself and the same went for Granny Reynolds who’d probably be killed by the shock anyway. He’d said Janet’s parents would be all right in Spain, but her sister would be for it in Milton Keynes, and Bridget’s mum had cried and agreed to stockpile soup but he’d run out of space in the downstairs toilet and started using his shed in the garden as WW3 HQ instead, his shed that he’d never let any of them go near before.

He’d opened it up, Bridget and Paul had watched him take a key out of his pocket and unlock the padlock, he’d made them wait till he was ready. All afternoon they’d traipsed across the garden carrying crates of tinned food, toilet roles and blankets, a bucket and the chair that he’d knocked the seat out of making their mum get angry for the first time ever and snap, Did he want to knock the whole bloody house down while he was at it. In and out of the shed, carrying the things that were going to keep them alive while the world went black and the air was poisoned and Bridget had wondered what was so special about her dad’s shed that he'd kept it locked, there wasn’t anything in the first place, only an old school trunk that he’d had since he was a boy. He seemed to have forgotten it was out of bounds, the way he went on cheerily saying he had everything organised, everything they’d need for longer than the government said they’d have to shelter for, he said he’d be ready for over a month inside if that’s what it took, he wasn’t worried at all. He’d even got three radios instead of two.

She’d stood in the shed and watched him counting the tins and toilet rolls and blankets. She’d spotted the sleeve of her white jersey sticking out the top of a bin liner, her church jumper with the red flowers she hated, as if there’d be church anymore.

She’d said, “What if we’re all at school?” and wondered what else he’d stolen from her room without asking.

He’d picked dirt out of his nails and said, “you’ll have to run,” and Paul had practised running through acid rain by putting his anorak over his head and running through the normal rain that had started coming down outside.

After tea he’d made them sit through the safety checklist as if it was a pub quiz only the prize was staying alive. When it came to the different siren sounds for Attack Warning and Fall-Out Warning and All Clear, she’d imagined hearing them in real life, hearing them as she stood in the dinner queue, her mum dishing out peas, giving her extra, not treating her any different to how she did at home even though Bridget had said, Don’t about a million times. She’d imagined the sudden blast of a siren cutting through the air and everyone running, not being orderly at all but throwing their trays in the air and scrambling over each other. She’d wondered if she’d mind her mum treating her like Bridget at home then, if she’d care if her mum scrambled over the other kids and took her hand. She’d imagined her mum remembering they had to get Paul, pulling her back across the playground even though the time was ticking and the bomb that was coming was ticking and there wouldn’t be time to save all of them. She’d imagined not wanting to let go, her mum’s face as she chose to die with Paul or live with Bridget, and the sirens wailing and her mum disappearing and Bridget turning and running for home. She’d wondered why school hadn’t stuck those checklists up on the wall in every classroom. That had been when she still believed her dad knew what he was talking about.

"a pub quiz only the prize was staying alive" : )

What a great peek into the angst-ridden uncertainties of our demise. Humans are so good at “what if’s,” all that planning for the worst case scenario, when too often the worst case isn’t a scenario at all but a long, drawn-out history of slow, unconscious simmering.