The last few months for Annabel had been about death and school, she hadn’t been back to Greenham. Christmas was at her mother’s; a sudden deterioration forced her there, her mother’s uptight fury that had surfaced as a cancer, that would kill her two weeks into the new term while Annabel explained the Pre-Raphaelites to twelve-year-olds, stepped up a gear in time for turkey and tinsel, causing Annabel to abandon her plans of slippers and sherry, pack up Reepicheep and Prince Caspian, and make the journey to High Barnett where she stayed with her from Christmas to new year. She ignored the bitterness, telephoned her sister, handed over the receiver and saw her mother smile. On January 1st she didn’t try to hide the newspaper on her lap, her hand on the photograph of forty-four women, their silhouettes a ring like the fence they’d climbed. She touched the photograph as if she could touch them, her Greenham sisters nothing like the sister in America who’d had all the children Annabel didn’t want, who hadn’t spent the night helping their mother to the bathroom five times, who’d said, Is that necessary? When Annabel had taken the phone into another room and told her it was time.

An honour that felt like a horror, their mother’s church would praise her, but only as it had damned her for not being there for her father. He’d died while she was at Goldsmiths. He’d gone down in the kitchen like a sack of coal on a Sunday afternoon while she, oblivious, explored the sweet pasture of her first and only girlfriend’s breasts; she hadn’t got the message until late the next day. Her mother proclaimed it was Annabel who’d been the cause. Never behaving, always running off, apparently she’d kissed a girl.

That night last December when Annabel had careered down darkened roads in Bridget’s father’s one-eyed Vauxhall Rover, Mr Reynolds chain smoking at the wheel, she’d been sure her life was over, more sure than when her mother had at last got through on the telephone to her digs in New Cross. Back then she’d had no idea her life would truly be over until her mother’s watery eyes had told her so; a daughter at art school had been bad enough when her father was alive, but now that he was dead it was over. Goldsmiths, the haven for Sodom and Gomorra was finished, she was to come home, she was to be more like her sister by which her mother meant give up everything.

Hurtling down the M3 last December, choking on cigarette fumes, she’d been sure that at best she’d be fired, at worst she’d go to prison. She’d watched Maureen lead Bridget’s dad away from the campfire, seen him get in his car and the policeman come over, watched the uniform lean into his window as the engine idled, the tap on the roof, been certain flashing lights would take the place of the one-eyed Vauxhall Rover as Bridget’s dad drove away; that he’d hand her over was as certain as his wheel spin in the mud. They were bound to be calling for back up, there’d be handcuffs and humiliation; she’d stayed up all night round the campfire praying quietly, hating herself for reverting to the God of her parents.

But nothing had happened. Bridget had stayed and Annabel had stayed, and they’d blockaded the base that freezing wet Monday and when Annabel had lost Bridget again the next day she’d assumed she’d gone back with Kate and that had been that. She’d gone into school on Tuesday, alert to the slightest movement of the art room door but it had only been breached by year ten followed by years seven and nine after lunch. No one in the staff room had spoken to her, the headmaster hadn’t called her to his office, Bridget had not surfaced in the playground or the dinner queue and that night she’d told Reepicheep and Prince Caspian that she couldn’t understand it.

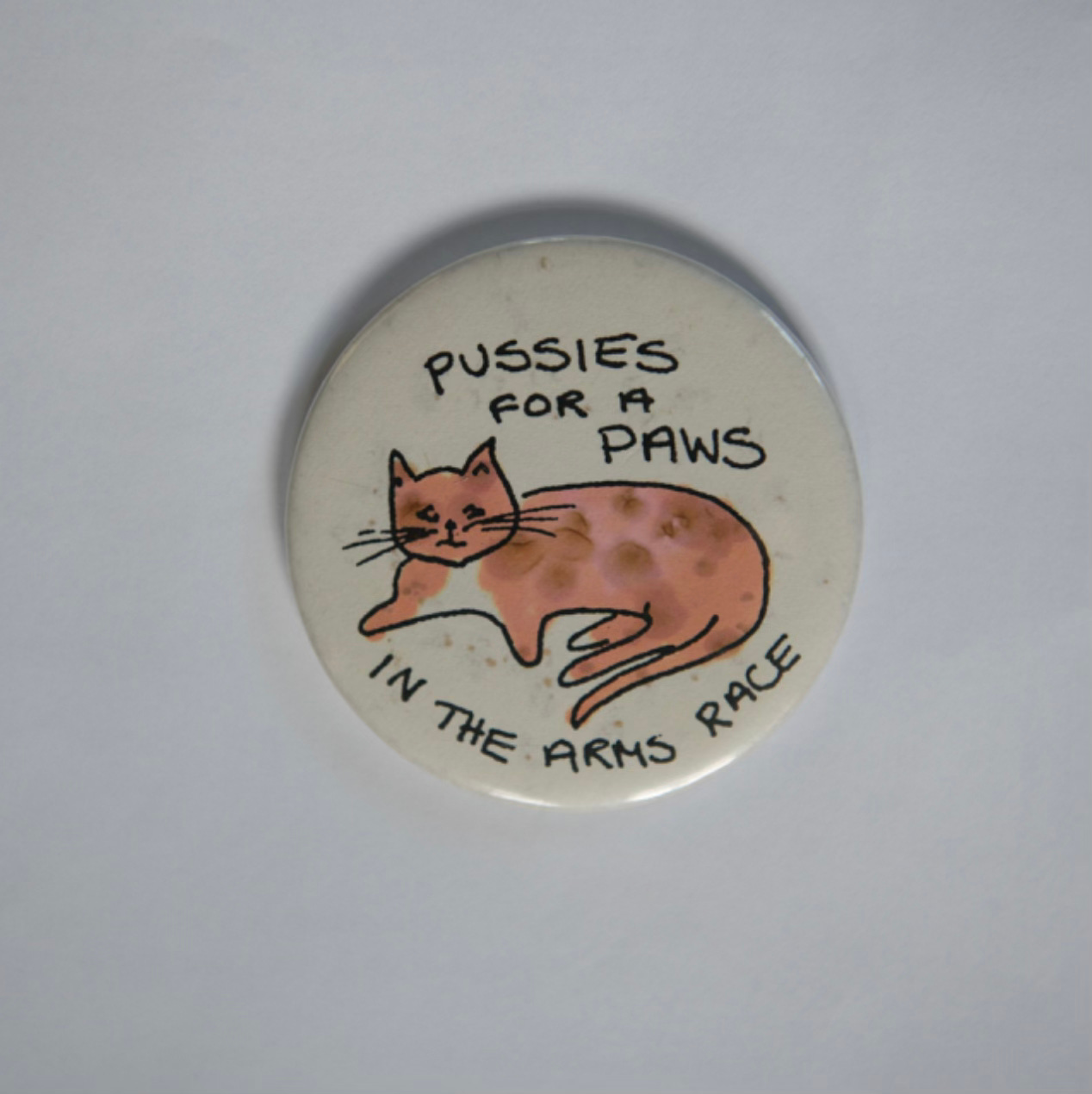

Christmas, new year, her mother died, her sister did not come back for the funeral but did for the reading of the will, for which she was disappointed. The house in High Barnett given to Annabel, she handed it to an agent to rent out. Her sister flew away. Spring arrived, daffodils replaced snowdrops, and with them a CND plan was hatched to link Greenham to Burghfield via Aldermaston in a human chain on April Fool’s Day that Annabel decided not to join. How could she when all she could think about was sex.

She was a hypocrite. She was in it for the wrong reasons, what sort of person wished secretly that Greenham would never end? A woman like Annabel. A woman who couldn’t stop thinking about the blonde spiked pierced goddess she’d seen blockading the base with Bridget on that freezing wet Monday last December. There were many beautiful women at Greenham, almost all women were beautiful to Annabel, the fact that they weren’t men, had none of the rough edges, had bulges of their own that made her want to take off all her clothes was enough but the blonde spiked pierced woman was a queen among them. Annabel had caught green eyes and moved to the other side of the fire in case she gave herself away.

The first and only time she’d had sex with a woman had been the first and only time she’d had sex with anyone, the ecstatic week of nakedness and wet sheets, her lust exploding out of her that ended with a phone call from her mother had been the best week of her life. She’d thought she’d got it made; a lonely suspicion that became a secret had been unpeeled as her clothes had been unpeeled, and she’d been set free. And then her father had died, and her mother had called, and Annabel had got back in her box. No woman had touched her since and she had touched no woman but herself, closing her bedroom door, turning off the lights so as not to frighten the mice.

She’d fantasised they shared a tent, a sleeping bag unzipping, two bodies warm against each other to the dripping rain outside. She imagined how they’d meet, a blockade or gathering firewood, those green eyes, she’d let her touch the piercings in her ear and then she’d let her touch elsewhere, all over, her hands roving, her fingers reaching, her tongue alight and between her own legs Annabel’s hand would move and she’d hope the mice didn’t hear. No, she could not go to Greenham even though at Greenham were the women who’d understand. Her heart wasn’t in missiles and Governments lying, it was lying in a bed with a blonde pierced Spanish woman whose voice she’d heard across the fire giving a lesson in Spanish history to Bridget.

She closed the art room door on the spring term and didn’t join the other teachers at the pub for the end of term piss up and would have spent April Fool’s Day alone with Reepicheep and Prince Caspian if the telephone hadn’t rung, if she hadn’t picked it up, if it wasn’t Kate Hilperton, calling.

Literary Obsessive champions Indie Lit Fiction. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is splendid: "He’d died while she was at Goldsmiths. He’d gone down in the kitchen like a sack of coal on a Sunday afternoon while she, oblivious, explored the sweet pasture of her first and only girlfriend’s breasts..."

“On January 1st she didn’t try to hide the newspaper on her lap, her hand on the photograph of forty-four women.” One of those lines I love. So much so quickly!

Holy damn, I love this story, Eleanor.