St Biddulph’s called Ray and Janet in for a chat. Janet thought they were going to say Bridget was out on her ear but the new young headmaster who everyone fancied got it into his tousled head that all young people needed to spread their wings.

“Their what?” Janet wore her best coat. The headmaster didn’t recognise her even though she served him his lunch every day.

“I hear Peggy Hilperton’s involved. They’re friends, aren’t they?”

“Not anymore,” Ray said under his breath as if he was going to murder Peggy Hilperton in her sleep.

“We thought if we left her to it she’d get it out of her system,” said Janet. “She’s got her O-Levels coming.”

“I think it’s smashing,” said the head.

“Our daughter’s playing truant,” said Ray.

“Peggy Hilperton’s been at pains to explain the relevance of their project.”

“What project?”

“For their History course work. Modern Suffragettes.”

“I’ll give you Modern suffragettes,” said Ray. “Our daughter’s off galivanting. It’s your job to haul her in. I’ve a good mind -” his foot jiggled on his knee, the worn-out sole plain for all to see. “I’ve a good mind -” but he never finished his sentence and Janet knew he wouldn’t. He hadn’t a good mind to do anything. He hadn’t called the authorities last December and he wasn’t going to now and she knew why. She’d sussed that out in sleepless nights lying next to him and his perfume.

“Where are we now,” said the head, flicking through his desk calendar.

“1983,” said Janet.

“He means, which month,” said Ray. He never did get Janet’s jokes, even at the beginning when he was so set convincing her to go out with him that he’d pretended to like paintings. He’d even driven her to night school every week before Bridget popped out, but Bridget had popped out early and Janet’s History of Art A-Level had gone to the wall.

“Why don’t we give those girls the week, and if they behave themselves, we could see our way to giving them Fridays till they’ve handed it in. I hear Miss Jenkins is a proponent, too. Perhaps we can arrange a school trip.”

Not on your nelly, thought Janet.

Outside in the playground, Ray said, “The man’s mad. One of those lefties. I’ve a good mind to report him.”

But Janet knew he wouldn’t do anything.

When they’d tried to get her home at Christmas, when they’d taken her to that dreadful pub, when Bridget had gone off to the toilet, Janet had said, “Do something Ray.” The Rokeby Arms wasn’t a place you’d take your dog, let alone your child. Ray had scraped the last bit of breadcrumb around the plate for what was left of his tartare sauce, popped it in his mouth and between chews said, “The girl’s got to do what the girl’s got to do.”

She’d lost her cool then. She’d snapped, “Don’t you trot out one of your phrases at me. You were all up in arms two weeks ago, you were ready to call the authorities.”

But Ray hadn’t replied because Bridget had returned and slumped down at the table. Janet had lit a cigarette and leaned toward her; she’d put her hand over her daughter’s hand and squeezed it. She’d said, “Have you got enough you know whats?” She knew what she was like. Always staining something. Bridget had looked at her as if she’d asked if she had two heads. How was she to know what kids were like these days? When she was a girl she hadn’t minded her mum knowing things, she’d told her everything, she’d even told her she was pregnant before she’d told Ray.

They’d left her there at the pub, Ray refusing to drive her anywhere unless it was Hampton Close, saying he was washing his hands of her he was that angry, and Christmas had been awful; it was never a hoot before but at least she’d had someone to laugh with when Ray’s mum settled into her machine gun volley of wind as soon as lunch was over. She’d cried into the pudding. She was sure that’s what had made it dry.

So Janet didn’t tell Ray she’d decided to try again, to go by herself to get her daughter back.

It was a freezing cold day and it had been raining and she packed her wellies and one of the old coats they kept for camping and made enough sandwiches to feed three Bridget’s and stuffed a box of Tampax and heavy flow pads in the bag with another jumper and three pairs of clean socks. A bus to Surbiton, a train to Newbury, she walked from the station and for a moment was distracted by the fence. She stood, the bag held to her chest like a baby, taken by the sight of its aggression, it’s barbed wire against sky, it’s concrete poles and padlocks and men in uniform, American soldiers whose eyes flicked over her as if she was just another one of the dirty women who crowded round the fire, whose camp washed up against them like so much muck on a beach. She hadn’t noticed it the first time, not really. Back before Christmas when Bridget was a runaway for only one night, she’d been so intent on getting her home that she’d hardly looked at the slash of metal, she’d been too distracted by Bridget’s hair, her face, the sudden state of her.

That day it had never crossed her mind that Bridget would stay, that she’d refuse her mum; quiet Bridget who spent most of her time in her room since she turned the corner of thirteen, who hadn’t raised a protest since Ray’s mother gave her a pink nightie for Christmas. But Janet had watched her daughter slouch off as if butter wouldn’t melt while Janet, trapped by tin mugs of tea with addled milk, had been too frightened to follow her.

She wouldn’t be afraid this time, she’d made a promise to herself, yet arriving at camp, a different feeling threatened to derail her plans, an outrage that flickered, a bursting she wanted to roar that she had to shut up, put down, supress if she wasn’t going to lose her head. She had to concentrate. Greenham was like a drug she couldn’t take. Everything about it felt illegal.

The women by the fire pointed Janet in the direction of a shelter that looked like something Paul would have made. She heard her laughter, unmistakable, and Janet’s heart lurched and she bent to see under the tarpaulin to find Bridget, half out of her sleeping bag, smoking something that didn’t look like anything Janet had smoked in her life.

“Is that drugs?”

“Mum.” She looked that shocked. Janet was glad. So she should.

Her friends went silent. Janet stood there bent over, one hand holding up the flap of sheeting, not knowing whether to come in or go out. It started to rain again.

“You should come in,” said a woman with piercings right up her nose.

“Not till I’ve had a word.” The rain trickled down her back and onto her neck.

“Mum.” Plaintiff this time, like she’d asked her to tidy her room.

Janet stood back as Bridget put on a pair of boots.

“I brought you these from home,” she held up the wellies Bridget only wore on camping trips.

“Got some already.” Bridget walked past her as if it was a given she’d follow.

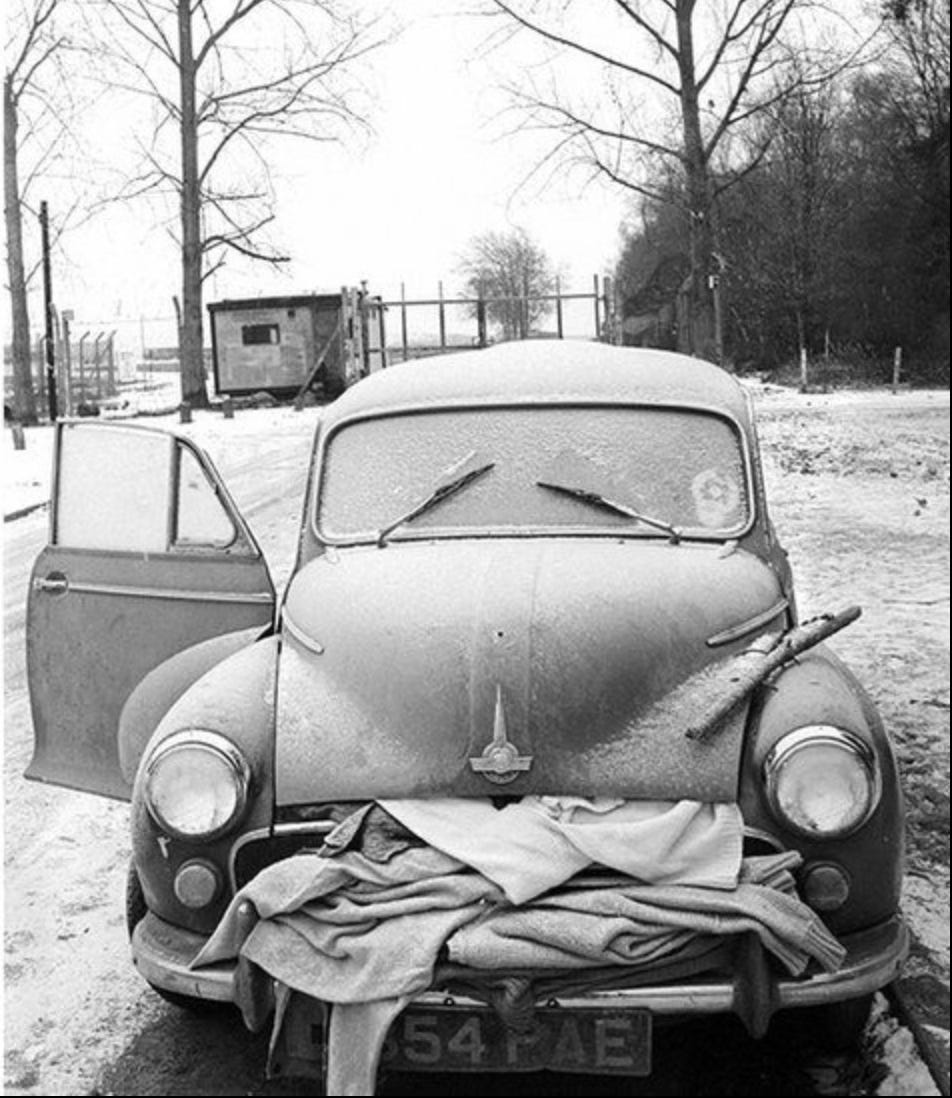

They found a car to sit in. It looked like a squirrel had been in there. The back was full of branches.

Janet got the sandwiches out. She’d wrapped them in the plastic innards from Paul’s variety pack that he was always allowed on his birthday. She was buggered if she was going to give over her best containers.

Tuna mayonnaise, Bridget flicked the slices of cucumber out the window.

“And I brought you some things.”

“I’m fine, mum.”

“Are you washing?” Janet wanted to get her in the bath and scrub that face till it was the peachy clean Bridget who used to put on her pyjamas and come and watch Dallas with her of a Saturday night.

“I told you I’m fine.”

“But are you taking care of yourself.” She’d promised herself she wouldn’t get emotional.

“It’s not up to you what I do anymore.”

“You’re still under my roof.”

“We’re under Maureen’s roof actually.” Bridget tapped the ceiling of the car.

“Don’t get smart with me.” She handed her another sandwich.

“Did you bring sanitary towels? We need them.”

“I just said I did. I’m not supplying the whole of Greenham Common, mind.”

“They use them for protection.”

“Well what else are they going to use them for?”

“Not down there, mum. For going over the fence.”

“Over my dead body, Bridget.”

Bridget ate her sandwich.

Janet said, “We’ve had school onto us again.”

1982: The Who's album “It's Hard” taps into early 1980s nuclear anxiety. The song “Why Did I Fall for That?” mentions the Doomsday Clock specifically: “Four minutes to midnight on a sunny day maybe if we smile the clock'll fade away maybe we can force the hands to just reverse.” Another song, “I've Known No War,” also expresses the fears and hopes for peace of those who came of age during the Cold War decades. Meanwhile the board game Trivial Pursuit becomes a cultural phenomenon. Later editions include this question: “What clock was created to adorn The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists?”

That clock was at four minutes to midnight back in 1983, it now is at ninety seconds. Reading Fallout I feel my outrage rising with each chapter. We haven't been this close ever....like Bridget's mum I feel about to burst, to join, to loose my head in favour of my heart.

I loved Dallas on a Saturday night! Had a real blast-from-the-past moment at this. But also a pang of sorrow for Janet. That terrifying feeling that your teenage offspring are walking away, becoming someone you didn’t foresee. I want to hug Janet and tell her it’s all good; it’ll be alright. That Bridget has a conscience and is doing the Life Lesson thing in the best way possible….